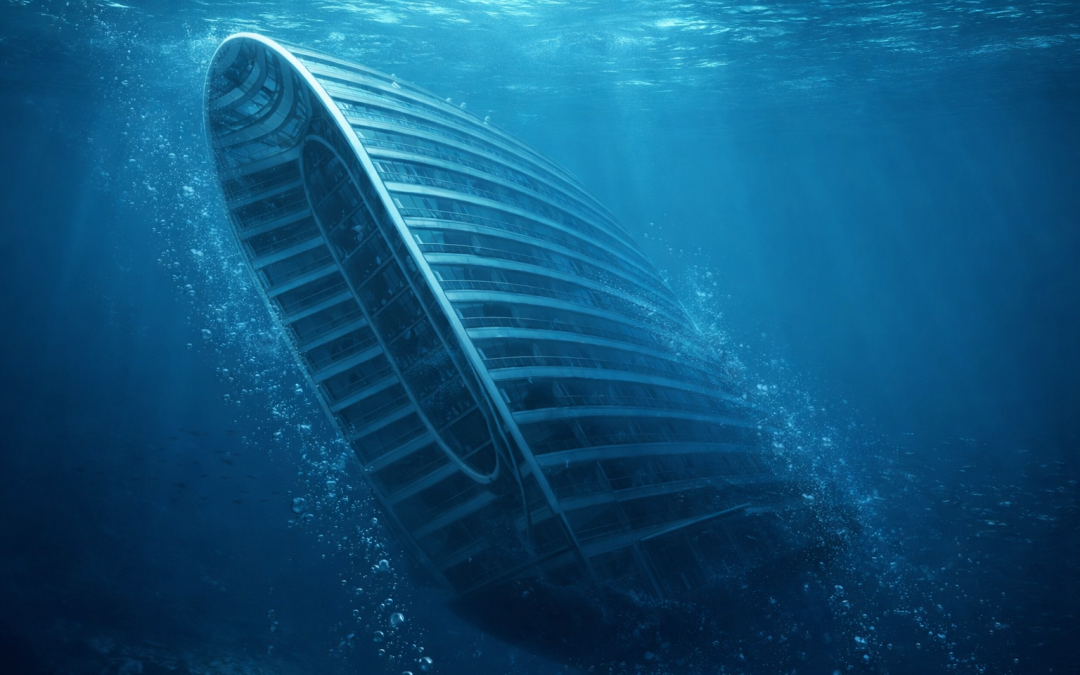

The public reaction to Fort Lauderdale’s proposed new City Hall was immediate and overwhelmingly negative. Some residents joked that it looked like a sinking ship or a Dyson fan. Others were far less charitable. But the reaction itself was the story. It was visceral, widespread, and driven by a sense that something significant had been decided without the public ever being meaningfully included.

What this project ultimately reveals is a widening disconnect between City Hall and the people it serves at a time when Fort Lauderdale is facing serious affordability pressures, failing infrastructure, and growing fiscal uncertainty. So, while the design grabbed attention, it is not the real issue. Cost, priorities and governance are.

How This Happened Matters

The way this project came together is just as troubling as the project itself. This was not the result of the City identifying its needs and then seeking competitive proposals to meet them. Instead, the process began with an unsolicited public-private partnership proposal.

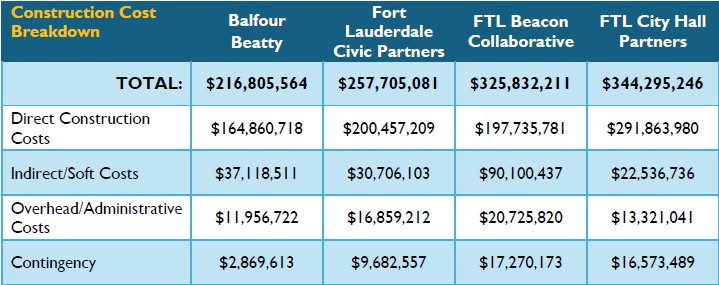

In May 2025, Meridiam Infrastructure North America submitted an unsolicited bid to design, finance, build, operate, and maintain a new City Hall. The City then opened a competitive window as required by Florida law, ultimately reviewing six proposals before selecting FTL City Hall Partners, which submitted the costliest design option.

That sequence is important. When developers drive the initial vision and define the solution, the City loses leverage. This project should have started with a traditional request for bids, anchored by clearly defined requirements. Square footage limits, durability standards, energy efficiency goals, resiliency benchmarks, and hard cost constraints should have been established before any design was ever put on the table. Instead, residents were presented with a finished concept and asked to comment after momentum had already been built.

At the December 2, 2025 meeting (at 12:30pm the Tuesday after Thanksgiving), only three residents spoke, all in opposition. That was not an endorsement of the project, most residents did not even realize such a consequential decision was underway.

The situation was compounded when nearly 2,000 pages of backup materials were uploaded just days before the vote to advance the project. It is unrealistic to suggest that residents, or even most commissioners, could have reasonably reviewed that volume of material in such a short time.

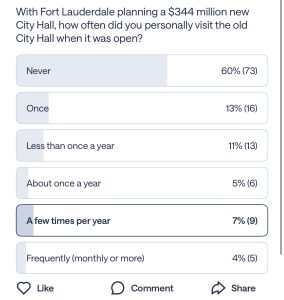

Once the project finally broke into the public conversation, the reaction was unmistakable. On December 11, 2025 the Sun Sentinel published 16 separate letters to the editor responding to the proposed City Hall, and they were overwhelmingly critical. On December 21, 2025, they published 16 more. Residents raised concerns about cost, priorities, design, and the lack of public engagement. On Nextdoor, a single post discussing the project generated nearly 200 responses, many echoing the same frustrations. This outpouring reflected what happens when people are finally made aware that a $344 million civic project is moving forward largely out of public view. I posted my own poll on Nextdoor asking residents how often the visit City Hall which received 122 votes:

A Price Tag That Defies Context

The most alarming aspect of this project remains its cost. At $344 million, the new City Hall represents an extraordinary expenditure for a city with roughly 3,000 employees, particularly one that routinely struggles to identify comparatively modest funding during budget deliberations and infrastructure planning discussions.

To put that number in perspective, the Broward County School Board, which oversees approximately 31,000 employees, has juggled with the thought of selling their downtown headquarters, long known as the Crystal Palace. That building is fully functional, includes commission chambers, and has served an organization nearly ten times the size of Fort Lauderdale’s government. Credible estimates suggest Fort Lauderdale could have offered to purchase or lease that existing building for a fraction of the cost, with estimates ranging from $30 million to $100 million.

Fort Lauderdale residents have also seen this movie before. The City’s new police headquarters was originally pitched at roughly $100 million, only to balloon to $140–150 million, with additional design and safety issues emerging along the way. That history matters, because it shows how major civic projects in Fort Lauderdale rarely come in at their initial price. When a project starts at $344 million in today’s construction market, after years of inflation, design revisions, and escalating labor costs, it is reasonable to assume that figure is a floor, not a ceiling. By the time financing costs, change orders, and long-term obligations are fully accounted for, taxpayers could easily be looking at a total cost that pushes well beyond half a billion dollars. Despite this, those on the commission supportive of the project seem to believe they will be able to shave the cost of the new city hall down to $200M. I wouldn’t count on that.

Who Bears the Risk

Fort Lauderdale has a well-documented affordability crisis. Working families are being priced out. Rent burdens continue to rise. Homelessness remains a persistent and growing challenge. Against that backdrop, committing to a nearly $350 million City Hall is difficult to reconcile with the lived realities of residents.

For years, Fort Lauderdale has relied heavily on development activity to balance its budget and keep millage rates in check. That strategy works only when development is booming.

Today, development has visibly cooled, the real estate market has softened, and broader economic conditions are uncertain. The City’s primary funding source remains ad valorem taxes. If revenues flatten, the gap does not disappear. It is filled through higher millage rates or reduced services. Moreover, the City’s primary source of revenue could dry up even absent any disruption in the real estate or development market, given the very real possibility that the elimination of property taxes in Florida could be advanced through a statewide ballot initiative.

With those risks plainly visible, City leadership has chosen to commit taxpayers to a massive long-term obligation without first securing broad public buy-in, exhausting lower-cost alternatives, or considering future revenue sources.

The “Reimagining City Hall” Workshops Tell a Very Different Story

City officials have repeatedly pointed to the City’s “Reimagining City Hall” workshops as evidence that public input meaningfully shaped the decision to move forward with the current project. That claim does not withstand even minimal scrutiny.

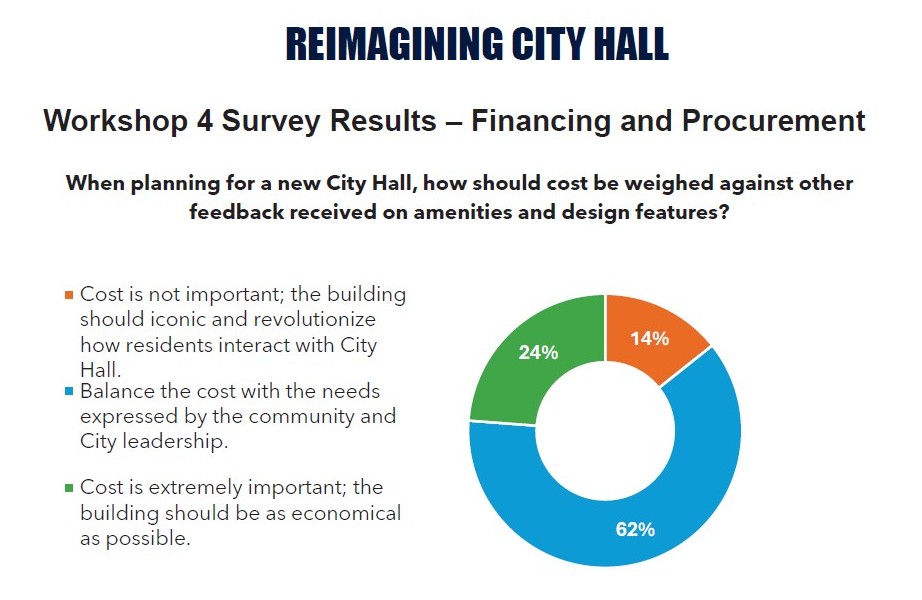

The workshop results are telling. When asked about cost priorities, only 14% of respondents said cost was not important and that the building should be iconic. A clear majority, 62%, said costs should be balanced with community needs and City leadership priorities. Another 24% said cost was extremely important and that the building should be as economical as possible.

Despite this, the Commission selected the most expensive proposal on the table.

The $344 million project chosen was approximately $20 million more than the next most expensive proposal and a staggering $128 million more than the lowest bid among the top four ranked submissions. That lowest bid came from Balfour Beatty, a nationally recognized construction firm with an established track record delivering large-scale projects. The public did not ask for the most expensive option. The data shows precisely the opposite.

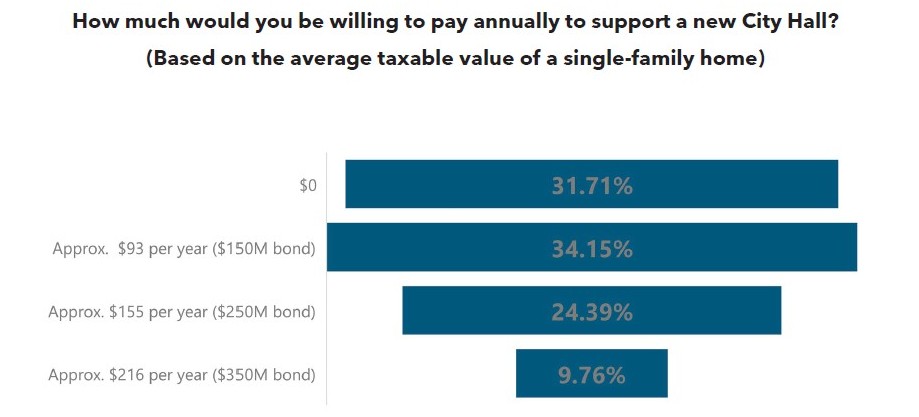

The workshops also provide a sobering glimpse into what this decision means for residents’ wallets. Only 9.76% of respondents said they would be willing to pay the roughly $216 per year for 30 years required to service a $350 million bond for City Hall. In contrast, 34.15% said they would support a $150 million bond costing about $93 per year, 24.39% said they might support a $250 million bond at approximately $155 per year, and 31.71% said they would not support a bond at all.

Put plainly, fewer than one in ten residents expressed support for the level of spending the Commission ultimately embraced which translates into roughly $216 per household per year for three decades (or about $6,500 total) for a single building, while sewer lines continue to rupture, neighborhoods flood, and basic infrastructure continues to deteriorate.

A City Manager on the Ball to the Chagrin of Certain Commissioners

In a moment of fiscal prudence, the City Manager introduced an unexpected alternative that exposed just how narrow the Commission’s thinking on City Hall has become.

In January 2026, City Manager Rickelle Williams circulated a memorandum to the City Commission outlining an opportunity to purchase 101 Tower at 101 NE 3rd Avenue for approximately $86 million, or roughly $372 per square foot. The item surfaced publicly during City Manager reports at the January 20, 2026 Commission meeting (shortly after midnight), after Commissioner Sorensen asked whether the Commission intended to discuss the memo.

Mayor Dean Trantalis dismissed the idea outright, asking, “Why would we do that?” He characterized the memo as an attempt to derail the current City Hall project and stated plainly, “I personally would not be in favor of that.” Commissioner Glassman echoed the sentiment, saying the opportunity was “too late” and expressing concern that development teams had already spent money responding to the City’s solicitation.

As Commissioner Herbst and Commissioner Ben Sorensen correctly pointed out, the City is not contractually bound to proceed. Negotiations are ongoing, and the City remains free to pause, reassess, or pursue alternative options at any point. Sorensen noted that the process does not preclude consideration of outside opportunities. Herbst went further, calling it “financially irresponsible” not to evaluate an option that could save taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars. Commissioner Pam Beasley-Pittman also indicated support to explore other options. The Mayor, however, reiterated “I am totally against it” and Commissioner Glassman echoed that position just as clearly, stating, “I am against it totally as well.”

Then, on February 2, 2026, the City Commission received yet another alternative: an offer to purchase the 1 E Broward Blvd building, a building exceeding 350,000 square feet, priced at approximately $350 per square foot, for a total purchase price of roughly $128 million. This property has already undergone several million dollars in renovations, is physically connected to the City’s existing parking structure, sits adjacent to major public transportation hubs including the bus station and Brightline, and occupies one of the most strategic intersections in Fort Lauderdale — Broward Boulevard and Andrews Avenue.

Faced with these options, refusing even to analyze them defies common sense.

A competent City Manager should be applauded for bringing forward alternatives, especially when they involve savings on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Yet Mayor Trantalis and Commissioner Glassman made clear they were not interested. They would prefer to press forward with a dramatically more expensive, developer-driven City Hall project — a monument no one asked for, at a price few support, promoted by the same small circle of lobbyists and insiders who always seem to get their way.

And it gets worse.

Calls to Fire the City Manager

Behind the scenes, frustration over the City Manager’s willingness to surface lower-cost alternatives has escalated into something more troubling. Speculation has grown that City Manager Rickelle Williams herself may now be targeted for firing, a pattern familiar to anyone who recalls how former City Auditor John Herbst was terminated after raising early warnings about the One Stop Shop project.

On January 29, 2026, members of the City Commission received an anonymous email laying out a detailed case for firing the City Manager. This was not a casual complaint. It was lengthy, carefully constructed, and plainly written by someone with deep knowledge of City Hall’s internal operations. Whatever grievances it claimed to raise, the timing and focus made the underlying trigger clear: the City Hall project and the City Manager’s refusal to treat it as untouchable.

The email accused Williams of cronyism, excessive spending, poor personnel decisions, and declining morale. It criticized hiring and restructuring decisions, questioned her management style, and alleged communication failures related to the One Stop FTL project. Most notably, it attacked her late-night introduction of alternative City Hall options, framing them as improper and destabilizing.

That critique does not hold up. Evaluating an $86 million acquisition as an alternative to a $344 million public-private partnership is responsible governance.

John Herbst, who knows firsthand the cost of challenging entrenched development interests at City Hall, responded publicly and directly:

“The City Manager has made a number of rookie mistakes, I grant you. You raise serious issues and I share some of those concerns. But bringing forward the option to purchase the 101 Building is not one of those. This is a great opportunity for the City to save taxpayers over $250 million.”

Herbst, who occupied an office in the 101 Building for 15 years, rejected claims that the building was deficient, calling them “an absolute falsehood.” He described the proposed new City Hall as “a vanity project and nothing more, to the assuage the egos of certain elected officials that talk constantly about iconic buildings.

The parallels to the One Stop Shop debacle are difficult to ignore. Herbst reminded readers that he was fired after warning that the deal was catastrophically bad for the City, a deal defended to the end by some of the same officials now resisting scrutiny of City Hall.

Herbst asked “[w]hat has changed [with the City Manager] in the past few months? That she actually pushed back against wasteful P3 projects that demonstrated that developers have a stranglehold over city spending?”

Holding a City Manager accountable for genuine missteps is appropriate. Targeting her for challenging a $344 million project that lacks public support is not.

Rickelle Williams has our support.

The immediate question is whether there are even three votes to take such action. At present, that seems unlikely, meaning the issue may never surface publicly in a meaningful way.

That uncertainty underscores how dysfunctional City Hall has become. Too often, decisions appear driven not by sound governance or the public interest, but by the personal priorities of certain elected officials who increasingly seem more concerned with their own interests and those of their favored lobbyists than with transparency, fiscal discipline, or accountability to the people they represent.

Who Will Go Down with the Ship?

On February 2, 2026, a reporter based in St. Petersburg also published a critical article highlighting what it described as eroding confidence in City Manager Rickelle Williams and questioning her direction and decision-making.

Taken together, readers should ask: who is pushing this information and manufacturing this narrative? Is this a coordinated effort by insiders unhappy with a leader willing to question costly projects, or is it reflective of broader concern in the community about governance and accountability? If this media campaign was coordinated by multiple members of the City Commission outside the public process, it raises serious Sunshine Law concerns that deserve scrutiny.

The irony of the proposed City Hall design is hard to miss. Residents joked that it looked like a sinking ship, and now the process behind it appears to be following the same course. The plan is taking on water: its cost defies context, its process excluded the public, and its priorities ignore affordability, failing infrastructure, and fiscal risk. When alternatives finally emerged, the response was not course correction but resistance. That leaves Fort Lauderdale with a simple question about leadership and governance.

When this plan finally sinks, who goes down with it? A City Manager willing to look for a safer course, or commissioners still clinging to a $344 million design residents never asked for and cannot afford?

Since the publication of this editorial, the City Commission has chosen not to explore any City Hall options beyond the original proposal. Mayor Trantalis, Commissioner Glassman, and Commissioner Pam Beasley-Pittman opposed considering alternative options, while Vice Mayor Herbst and Commissioner Sorensen supported further exploration as a prudent step to protect taxpayers. Why the Commission would choose to limit its own options and decline to investigate the potential to save hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars is bewildering.

I am completely opposed to the proposed city hall monstrosity which will likely cost $475M after the change orders, building errors, etc. We all know this tune well. I applaud all the people who came up with cost saving alternatives, including the City manager. After reading the full article, I see only 2 yes votes for continuing with new build, and the remaining votes for seeking a purchase of an existing building. That means the new build fails. I plead with the remaining city board members to stick with their no votes and explore the purchase of existing buildings for the sake of the residents of Fort Lauderdale. Don’t be bullied by Trantalis and Glassman. We just can’t continue with wasteful spending when so many are struggling.

Unfortunately, at today’s City Commission Conference Meeting, Commissioner Pam Beasley-Pittman reversed her prior position and joined Mayor Trantalis and Commissioner Glassman in opposing any further investigation into these potential purchasing opportunities. As a result, the Commission will move full steam ahead with the most expensive option, despite the availability of significantly cheaper alternatives.

– John Rodstrom III

I wonder why the voters of Ft.Lauderdale never get to vote on important issues, i.e. city building contruction, beach basketball courts, trees on Las Olas, etc.,?