Clinging to a Sinking Ship: Fort Lauderdale’s $344 Million City Hall and the City Manager Fallout

The public reaction to Fort Lauderdale’s proposed new City Hall was immediate and overwhelmingly negative. Some residents joked that it looked like a sinking ship or a Dyson fan. Others were far less charitable. But the reaction itself was the story. It was visceral, widespread, and driven by a sense that something significant had been decided without the public ever being meaningfully included.

What this project ultimately reveals is a widening disconnect between City Hall and the people it serves at a time when Fort Lauderdale is facing serious affordability pressures, failing infrastructure, and growing fiscal uncertainty. So, while the design grabbed attention, it is not the real issue. Cost, priorities and governance are.

How This Happened Matters

The way this project came together is just as troubling as the project itself. This was not the result of the City identifying its needs and then seeking competitive proposals to meet them. Instead, the process began with an unsolicited public-private partnership proposal.

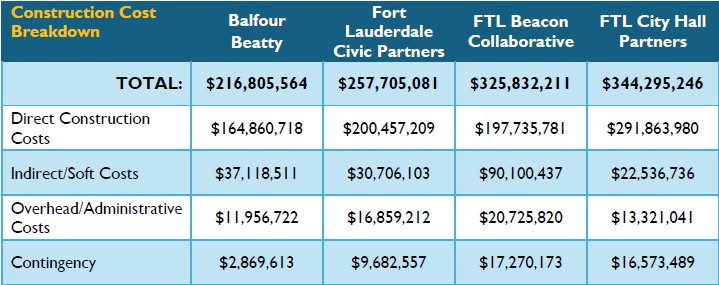

In May 2025, Meridiam Infrastructure North America submitted an unsolicited bid to design, finance, build, operate, and maintain a new City Hall. The City then opened a competitive window as required by Florida law, ultimately reviewing six proposals before selecting FTL City Hall Partners, which submitted the costliest design option.

That sequence is important. When developers drive the initial vision and define the solution, the City loses leverage. This project should have started with a traditional request for bids, anchored by clearly defined requirements. Square footage limits, durability standards, energy efficiency goals, resiliency benchmarks, and hard cost constraints should have been established before any design was ever put on the table. Instead, residents were presented with a finished concept and asked to comment after momentum had already been built.

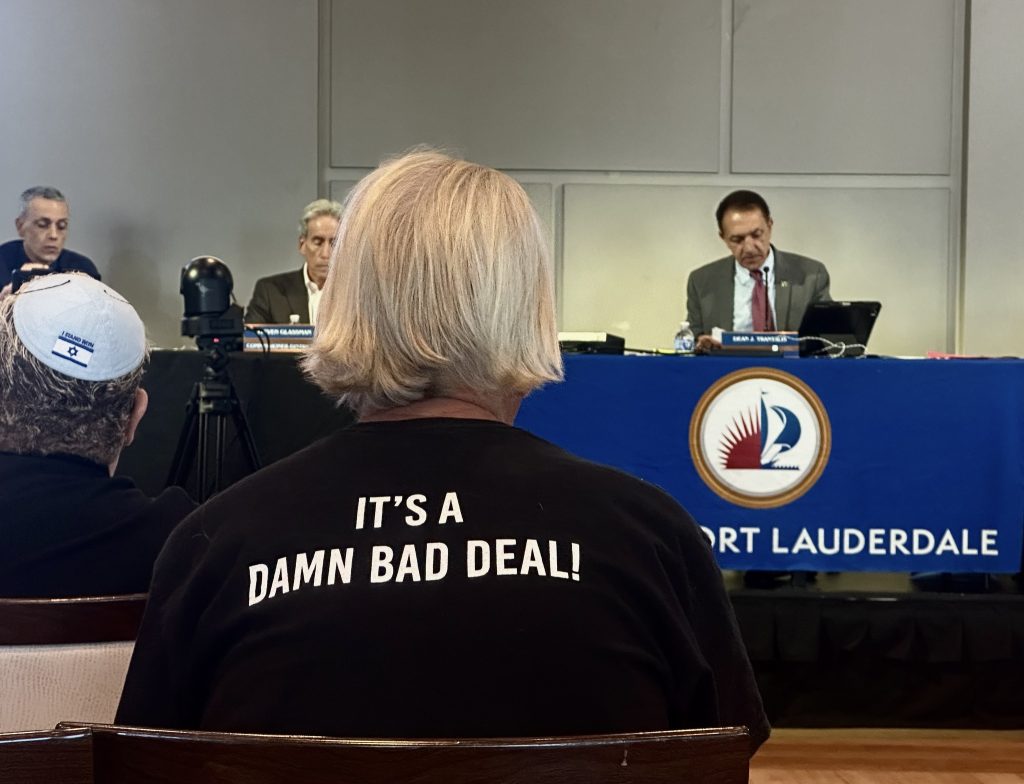

At the December 2, 2025 meeting (at 12:30pm the Tuesday after Thanksgiving), only three residents spoke, all in opposition. That was not an endorsement of the project, most residents did not even realize such a consequential decision was underway.

The situation was compounded when nearly 2,000 pages of backup materials were uploaded just days before the vote to advance the project. It is unrealistic to suggest that residents, or even most commissioners, could have reasonably reviewed that volume of material in such a short time.

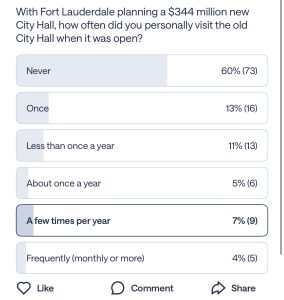

Once the project finally broke into the public conversation, the reaction was unmistakable. On December 11, 2025 the Sun Sentinel published 16 separate letters to the editor responding to the proposed City Hall, and they were overwhelmingly critical. On December 21, 2025, they published 16 more. Residents raised concerns about cost, priorities, design, and the lack of public engagement. On Nextdoor, a single post discussing the project generated nearly 200 responses, many echoing the same frustrations. This outpouring reflected what happens when people are finally made aware that a $344 million civic project is moving forward largely out of public view. I posted my own poll on Nextdoor asking residents how often they visit City Hall which received 122 votes:

A Price Tag That Defies Context

The most alarming aspect of this project remains its cost. At $344 million, the new City Hall represents an extraordinary expenditure for a city with roughly 3,000 employees, particularly one that routinely struggles to identify comparatively modest funding during budget deliberations and infrastructure planning discussions.

To put that number in perspective, the Broward County School Board, which oversees approximately 31,000 employees, has juggled with the thought of selling their downtown headquarters, long known as the Crystal Palace. That building is fully functional, includes commission chambers, and has served an organization nearly ten times the size of Fort Lauderdale’s government. Credible estimates suggest Fort Lauderdale could have offered to purchase or lease that existing building for a fraction of the cost, with estimates ranging from $30 million to $100 million.

Fort Lauderdale residents have also seen this movie before. The City’s new police headquarters was originally pitched at roughly $100 million, only to balloon to $140–150 million, with additional design and safety issues emerging along the way. That history matters, because it shows how major civic projects in Fort Lauderdale rarely come in at their initial price. When a project starts at $344 million in today’s construction market, after years of inflation, design revisions, and escalating labor costs, it is reasonable to assume that figure is a floor, not a ceiling. By the time financing costs, change orders, and long-term obligations are fully accounted for, taxpayers could easily be looking at a total cost that pushes well beyond half a billion dollars. Despite this, those on the commission supportive of the project seem to believe they will be able to shave the cost of the new city hall down to $200M. I wouldn’t count on that.

Who Bears the Risk

Fort Lauderdale has a well-documented affordability crisis. Working families are being priced out. Rent burdens continue to rise. Homelessness remains a persistent and growing challenge. Against that backdrop, committing to a nearly $350 million City Hall is difficult to reconcile with the lived realities of residents.

For years, Fort Lauderdale has relied heavily on development activity to balance its budget and keep millage rates in check. That strategy works only when development is booming.

Today, development has visibly cooled, the real estate market has softened, and broader economic conditions are uncertain. The City’s primary funding source remains ad valorem taxes. If revenues flatten, the gap does not disappear. It is filled through higher millage rates or reduced services. Moreover, the City’s primary source of revenue could dry up even absent any disruption in the real estate or development market, given the very real possibility that the elimination of property taxes on homesteaded properties in Florida could be advanced through a statewide ballot initiative.

With those risks plainly visible, City leadership has chosen to commit taxpayers to a massive long-term obligation without first securing broad public buy-in, exhausting lower-cost alternatives, or considering future revenue sources.

The “Reimagining City Hall” Workshops Tell a Very Different Story

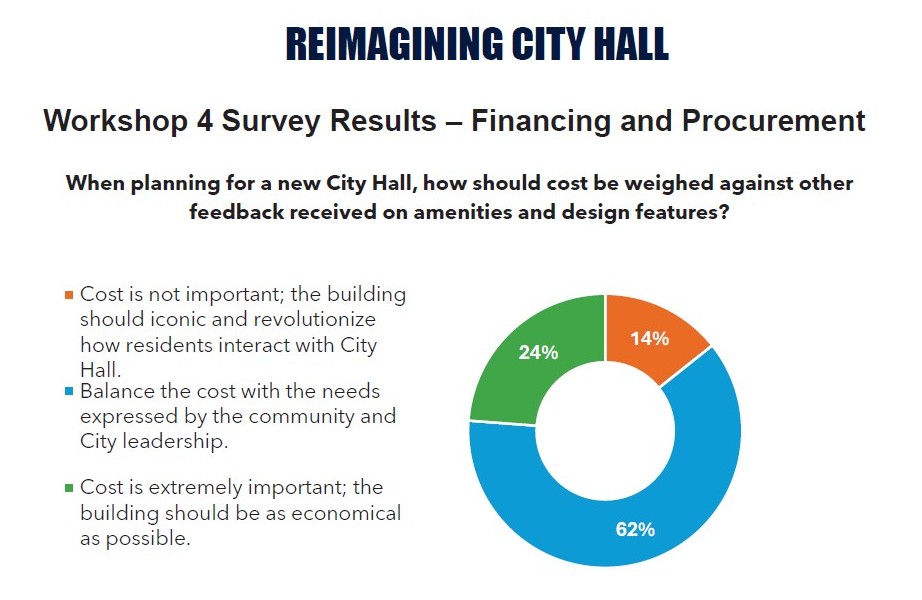

City officials have repeatedly pointed to the City’s “Reimagining City Hall” workshops as evidence that public input meaningfully shaped the decision to move forward with the current project. That claim does not withstand even minimal scrutiny.

The workshop results are telling. When asked about cost priorities, only 14% of respondents said cost was not important and that the building should be iconic. A clear majority, 62%, said costs should be balanced with community needs and City leadership priorities. Another 24% said cost was extremely important and that the building should be as economical as possible.

Despite this, the Commission selected the most expensive proposal on the table.

The $344 million project chosen was approximately $20 million more than the next most expensive proposal and a staggering $128 million more than the lowest bid among the top four ranked submissions. That lowest bid came from Balfour Beatty, a nationally recognized construction firm with an established track record delivering large-scale projects. The public did not ask for the most expensive option. The data shows precisely the opposite.

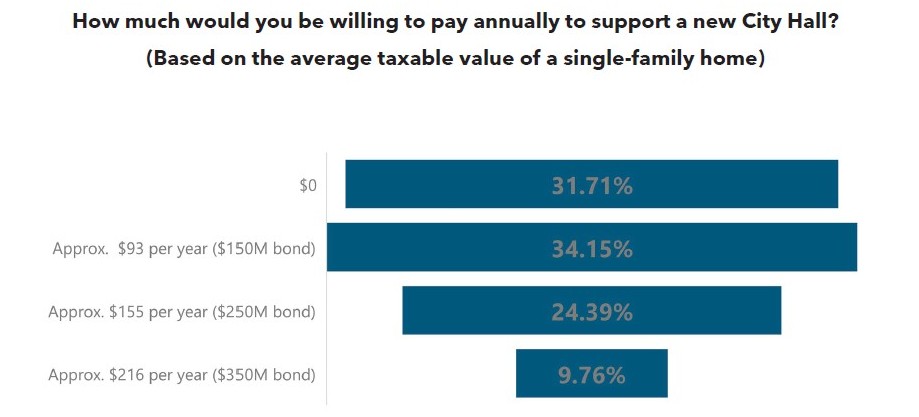

The workshops also provide a sobering glimpse into what this decision means for residents’ wallets. Only 9.76% of respondents said they would be willing to pay the roughly $216 per year for 30 years required to service a $350 million bond for City Hall. In contrast, 34.15% said they would support a $150 million bond costing about $93 per year, 24.39% said they might support a $250 million bond at approximately $155 per year, and 31.71% said they would not support a bond at all.

Put plainly, fewer than one in ten residents expressed support for the level of spending the Commission ultimately embraced which translates into roughly $216 per household per year for three decades (or about $6,500 total) for a single building, while sewer lines continue to rupture, neighborhoods flood, and basic infrastructure continues to deteriorate.

A City Manager on the Ball to the Chagrin of Certain Commissioners

In a moment of fiscal prudence, the City Manager introduced an unexpected alternative that exposed just how narrow the Commission’s thinking on City Hall has become.

In January 2026, City Manager Rickelle Williams circulated a memorandum to the City Commission outlining an opportunity to purchase 101 Tower at 101 NE 3rd Avenue for approximately $86 million, or roughly $372 per square foot. The item surfaced publicly during City Manager reports at the January 20, 2026 Commission meeting (shortly after midnight), after Commissioner Sorensen asked whether the Commission intended to discuss the memo.

Mayor Dean Trantalis dismissed the idea outright, asking, “Why would we do that?” He characterized the memo as an attempt to derail the current City Hall project and stated plainly, “I personally would not be in favor of that.” Commissioner Glassman echoed the sentiment, saying the opportunity was “too late” and expressing concern that development teams had already spent money following the unsolicited bid process.

As Commissioner Herbst and Commissioner Ben Sorensen correctly pointed out, the City is not contractually bound to proceed. Negotiations are ongoing, and the City remains free to pause, reassess, or pursue alternative options at any point. Sorensen noted that the process does not preclude consideration of outside opportunities. Herbst went further, calling it “financially irresponsible” not to evaluate an option that could save taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars. Commissioner Pam Beasley-Pittman also indicated support to explore other options. The Mayor, however, reiterated “I am totally against it” and Commissioner Glassman echoed that position just as clearly, stating, “I am against it totally as well.”

Then, on February 2, 2026, the City Commission received yet another alternative: an offer to purchase the 1 E Broward Blvd building, a building exceeding 350,000 square feet, priced at approximately $350 per square foot, for a total purchase price of roughly $128 million. This property has already undergone several million dollars in renovations, is physically connected to the City’s existing parking structure, sits adjacent to major public transportation hubs including the bus station and Brightline, and occupies one of the most strategic intersections in Fort Lauderdale — Broward Boulevard and Andrews Avenue.

Faced with these options, refusing even to analyze them defies common sense.

A competent City Manager should be applauded for bringing forward alternatives, especially when they involve savings on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Yet Mayor Trantalis and Commissioner Glassman made clear they were not interested. They would prefer to press forward with a dramatically more expensive, developer-driven City Hall project — a monument no one asked for, at a price few support, promoted by the same small circle of lobbyists and insiders who always seem to get their way.

And it gets worse.

Calls to Fire the City Manager

Behind the scenes, frustration over the City Manager’s willingness to surface lower-cost alternatives has escalated into something more troubling. Speculation has grown that City Manager Rickelle Williams herself may now be targeted for firing, a pattern familiar to anyone who recalls how former City Auditor John Herbst was terminated after raising early warnings about the One Stop Shop project.

On January 29, 2026, members of the City Commission received an anonymous email laying out a detailed case for firing the City Manager. This was not a casual complaint. It was lengthy, carefully constructed, and plainly written by someone with deep knowledge of City Hall’s internal operations. Whatever grievances it claimed to raise, the timing and focus made the underlying trigger clear: the City Hall project and the City Manager’s refusal to treat it as untouchable.

The email accused Williams of cronyism, excessive spending, poor personnel decisions, and declining morale. It criticized hiring and restructuring decisions, questioned her management style, and alleged communication failures related to the One Stop FTL project. Most notably, it attacked her late-night introduction of alternative City Hall options, framing them as improper and destabilizing.

That critique does not hold up. Evaluating an $86 million acquisition as an alternative to a $344 million public-private partnership is responsible governance.

John Herbst, who knows firsthand the cost of challenging entrenched development interests at City Hall, responded publicly and directly:

“The City Manager has made a number of rookie mistakes, I grant you. You raise serious issues and I share some of those concerns. But bringing forward the option to purchase the 101 Building is not one of those. This is a great opportunity for the City to save taxpayers over $250 million.”

Herbst, who occupied an office in the 101 Building for 15 years, rejected claims that the building was deficient, calling them “an absolute falsehood.” He described the proposed new City Hall as “a vanity project and nothing more, to the assuage the egos of certain elected officials that talk constantly about iconic buildings.

The parallels to the One Stop Shop debacle are difficult to ignore. Herbst reminded readers that he was fired after warning that the deal was catastrophically bad for the City, a deal defended to the end by some of the same officials now resisting scrutiny of City Hall.

Herbst asked “[w]hat has changed [with the City Manager] in the past few months? That she actually pushed back against wasteful P3 projects that demonstrated that developers have a stranglehold over city spending?”

Holding a City Manager accountable for genuine missteps is appropriate. Targeting her for challenging a $344 million project that lacks public support is not.

Rickelle Williams has our support.

The immediate question is whether there are even three votes to take such action. At present, that seems unlikely, meaning the issue may never surface publicly in a meaningful way.

That uncertainty underscores how dysfunctional City Hall has become. Too often, decisions appear driven not by sound governance or the public interest, but by the personal priorities of certain elected officials who increasingly seem more concerned with their own interests and those of their favored lobbyists than with transparency, fiscal discipline, or accountability to the people they represent.

Who Will Go Down with the Ship?

On February 2, 2026, a reporter based in St. Petersburg also published a critical article highlighting what it described as eroding confidence in City Manager Rickelle Williams and questioning her direction and decision-making.

Taken together, readers should ask: who is pushing this information and manufacturing this narrative? Is this a coordinated effort by insiders unhappy with a leader willing to question costly projects, or is it reflective of broader concern in the community about governance and accountability? If this media campaign was coordinated by multiple members of the City Commission outside the public process, it raises serious Sunshine Law concerns that deserve scrutiny.

The irony of the proposed City Hall design is hard to miss. Residents joked that it looked like a sinking ship, and now the process behind it appears to be following the same course. The plan is taking on water: its cost defies context, its process excluded the public, and its priorities ignore affordability, failing infrastructure, and fiscal risk. When alternatives finally emerged, the response was not course correction but resistance. That leaves Fort Lauderdale with a simple question about leadership and governance.

When this plan finally sinks, who goes down with it? A City Manager willing to look for a safer course, or commissioners still clinging to a $344 million design residents never asked for and cannot afford?

Since the publication of this editorial, the City Commission has chosen not to explore any City Hall options beyond the original proposal. Mayor Trantalis, Commissioner Glassman, and Commissioner Pam Beasley-Pittman opposed considering alternative options, while Vice Mayor Herbst and Commissioner Sorensen supported further exploration as a prudent step to protect taxpayers. Why the Commission would choose to limit its own options and decline to investigate the potential to save hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars is bewildering.

Why Fort Lauderdale Residents Should Be Outraged Over the One Stop Shop Fiasco

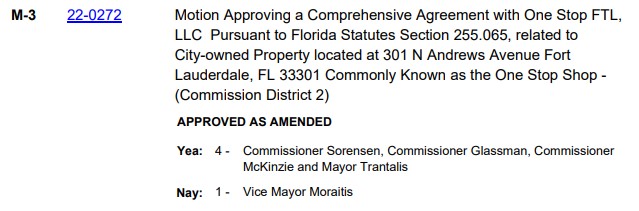

On May 6, 2025, the City Commission finally had enough. After years of empty promises and a fenced-off city owned 3.3-acre lot in the heart of Fort Lauderdale, they declared the One Stop Shop developer in default. The reason? Failure to prove financing.

Three days later, the City Attorney’s office sent a formal notice of default, giving the developer 30 days to cure. That should have been the beginning of the end for a project that’s been all smoke and no shovels since its approval in 2022.

But this is Fort Lauderdale, where accountability often gets lost in the paperwork shuffle. On August 27—110 days after the default notice—the Interim City Attorney quietly issued a “Notice of Partial Cure.” His reasoning? The developer had, in his view, provided the proper proof of financing documents.

Here’s the kicker: staff and the City Auditor’s Office strongly disagree.

A Cure Nobody Believes

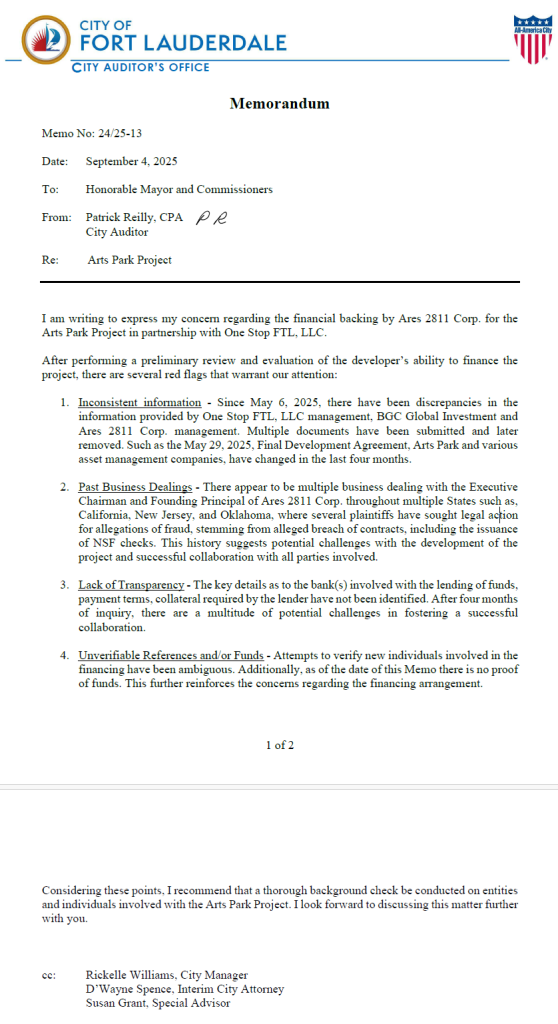

Within days, the cracks in the Interim City Attorney’s decision started to show. On September 4, City Auditor Patrick Reilly sent a memo warning of “several red flags,” including “inconsistent information,” “past business dealings,” “lack of transparency” and “unverifiable references and/or funds.” His blunt conclusion:

“As of the date of this memo there is no proof of funds. This further reinforces the concerns regarding the financing arrangement.”

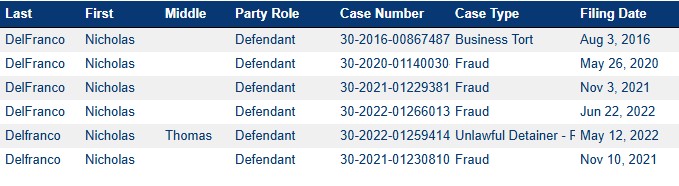

The City Auditor’s September 4 memo also confirms what we reported months ago: Nicholas Thomas Del Franco, the man now slated to control a majority stake in this public land deal, comes with a troubling history. City Auditor Patrick Reilly’s review flagged Del Franco’s “multiple business dealings” in California, New Jersey, and Oklahoma, where plaintiffs have pursued legal action over allegations of fraud, breach of contract, and even bounced checks. This language mirrors the findings FTL Politics published back in May, when we detailed a dozen lawsuits filed against Del Franco across multiple states, painting what we believe to be a consistent picture of risk and unreliability (one of the best editorials we’ve done if you haven’t read it). That the city’s own auditor has now raised the same red flags makes it impossible to dismiss these concerns as speculation. The memo concludes by recommending a “thorough background check be conducted on entities and individuals involved[.]”

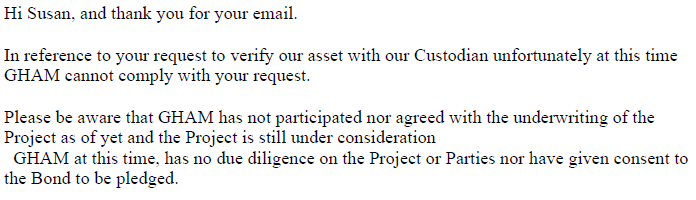

Special Advisor Susan Grant also raised alarms. In an August 27 memo, she noted that Gauntlet Holdings Asset Management (“GHAM”), one of the supposed financiers, “had not previously been identified” as part of the deal.

Less than two weeks later, Gauntlet confirmed Grant’s instincts. In a September 8 email, the firm told the City it “has not participated or agreed with the underwriting of the project as of yet, and the project is still under consideration.”

So, the Interim City Attorney issued a partial cure letter saying financing had been proven—while the City’s own staff was scrambling to verify if the financiers even really knew about the project.

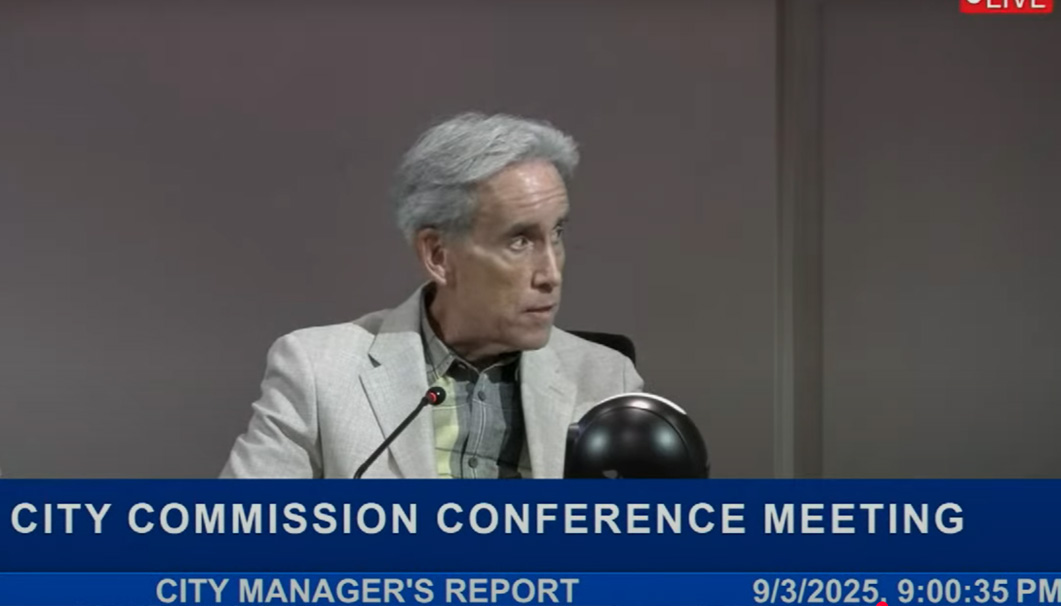

The September 3 Meeting: Red Flags Everywhere

Not long after the Commission returned from its summer break, it was clear things were spiraling. Commissioner Sorensen brought up the item at the September 3 meeting with a warning:

“Mayor, I have major concerns, as I have talked to staff they have significant concerns.”

City Auditor Patrick Reilly was more direct:

“I don’t know what bank they are dealing with, I don’t know the terms, and I don’t know when that money is coming . . . The four documents we have have not satisfied me that we actually have the funding. I would like to confirm the funding.”

He revealed he even called London to speak to a man listed in financing documents, only to find that he had “no idea who Jeffrey John [the developer] was.”

Commissioner Herbst, a CPA, CFO, and former City Auditor, was floored:

“You are telling me the guy who is providing $140M in financing has no idea who he’s giving it to?” . . . “This is as bad as the first time when I asked the [the developer] who he is borrowing the money from and he didn’t even know the name of the company.”

Commissioner Beasley-Pittman said what many were thinking:

“Who does business like this? . . . Better Business Bureau, police, somebody, this is fraud.”

Glassman’s “Two Towers” Defense, The Mayor’s Breaking Point

Only one commissioner seemed unbothered: Steve Glassman, who has championed this deal from the start.

“Financing is there, they are ready to go,” Glassman said, insisting that the project was “excellent” and suggesting critics just didn’t understand the process.

But even Mayor Dean Trantalis, once a vocal supporter, had enough:

“I have been in favor of this project from day one, but it’s not happening. It’s a flim-flam. Come on, either do it or get off the pot.”

The Mayor pointed out that the developer hasn’t even provided the $250,000 good-faith payment promised in May:

“If they can’t come up with $250,000, how are they going to come up with $140 million?”

Commissioner Glassman has long defended this deal with a dire warning: if this project doesn’t happen, downtown Fort Lauderdale will get “two more high-rises with no park space.”

But this claim is a red herring. The land in question is city-owned public land. Any project on it would require full City Commission approval, just like this project did. There is no active plan, submission, or proposal for two towers on this site, and no developer could simply build there without the city’s blessing.

By framing this as a choice between a questionable deal and phantom towers, Glassman is misrepresenting the city’s options. The real choice is between giving away prime public land to a developer with unverified financing or reclaiming it for the public good.

Contracts Work Both Ways

In today’s Sun Sentinel op-ed, developer Jeff John claims the City of Fort Lauderdale is undermining its reputation by “reneging” on a signed agreement. But this narrative ignores a fundamental reality: contracts work both ways. The City Commission, as steward of public land, has not only the right but the obligation to enforce agreements, especially when they determine a developer has failed to meet clearly defined terms.

The One Stop contract was not a blank check. It included deadlines and financing requirements designed to protect taxpayers. In our opinion, those obligations have not been met. Hell, the agreement required proof of financing within 90 days of it being signed back in 2022… The project remains stalled three years later, with no verified financing (according to the City Auditor), a missing $250,000 “good faith” payment, and mounting red flags identified by city staff and the City Auditor. Enforcing those terms is not a “political agenda.” It’s basic governance.

At the very end of Jeff John’s op-ed, there’s an editor’s note: “Fort Lauderdale declined to respond to John’s assertions. The city cited a letter from John’s attorneys that raises the possibility of legal action against the city.” That’s right — after years of missed deadlines, incomplete financing proof, and a default notice, the developer is now threatening to sue Fort Lauderdale for daring to hold him accountable. Some partner.

If Fort Lauderdale were to ignore blatant breaches and continue extending lifelines, that would erode trust in the city’s leadership and send a dangerous message to future investors: rules don’t matter here.

A Pattern of Excuses

Let’s recap:

- The Commission voted for default in May.

- The Interim City Attorney quietly issued a partial cure in August, claiming financing had been proven.

- Staff and the Auditor’s Office now openly say financing has not been confirmed.

- Commissioners are being told to give the developer more time—again.

This is the same song-and-dance we’ve seen for three years: delay, excuse, repeat. The site is still fenced off. There’s still no shovel in the ground. And now there’s even more confusion about who’s really bankrolling this project.

As the Sun Sentinel wrote:

“Time to bring down the curtain on this years-long farce . . . Unless he stands in the middle of Broward Boulevard next week holding $140 million in cash, Arts Park appears dead or dying.”

Enough Slack

Why is the Interim City Attorney playing defense for a project the City Auditor openly says is full of “red flags?” Why was a partial cure issued without it being discussed at a city commission meeting and without independent confirmation of financing?

And now, the clock is ticking again. The One Stop Shop project is scheduled to be back on the agenda at tomorrow’s City Commission conference meeting at 1:30 p.m.. Residents should be watching closely (and attend if possible)—because once again, the future of this public land is on the line.

The Commission owes taxpayers an answer. Fort Lauderdale has waited long enough.

Rescind the partial cure. Terminate the agreement. Reclaim the land. Restore some integrity to city government.

One Stop FTL: Fort Lauderdale’s $35 Million Public Land Deal Just Went from Bad to Worse

Enjoy our editorials? Check out our new podcast above!

For more than three years, a fenced-off 3.3-acre lot in the heart of downtown Fort Lauderdale has sat dormant. Once the city’s permitting office and long envisioned as a public park, it is now the subject of public outrage and scandal. The culprit: a failed public-private partnership known as One Stop FTL. What began as an unsolicited proposal from nightlife promoter Jeff John has devolved into a case study in poor governance, backroom lobbying, and phantom financing.

The City owned One Stop Shop land, worth an estimated $35 million, was handed over to a private developer through a 99-year control agreement that allows for no property taxes and requires no rent until after a certificate of occupancy is issued. While this in and of itself is rather common, the fact there is no deadline to commence or complete construction is not. So until something is built (if it ever is) and gets its certificate of occupancy, the developer owes the city nothing. This explains why no shovels have hit the ground. As long as the developer avoids triggering the C/O, the site remains a rent-free holding, and a prime downtown parcel sits fenced off, unused.

Phantom Financing, Real Consequences

Residents, journalists, and even (some) commissioners have demanded answers. But as of today, we’ve seen no credible proof of financing. In fact, when pressed during a May 2025 meeting, developer Jeff John couldn’t provide the supposed “commitment letter” he had shown staff. This editorial site revealed a suspect financing letter obtained through a public records request from a New York company with a residential address called Ares 2811, Corp. The Sun-Sentinel commented that the letter was suspect and looked “phony.” At the last meeting on the issue, the developer couldn’t even say who his financing was from and was unsure if he had an arrangement with BGC Group or BCG Group. He brought another individual along who had just as few answers.

When Commissioner Herbst asked directly if the funds were coming from BGC Group, formerly Cantor Fitzgerald, the response was stunning: “I have to verify that.”

It’s also worth remembering that then City Auditor John Herbst was fired by Mayor Trantalis, Commissioner Glassman, and Commissioner Sorensen, largely because he raised concerns about this very deal. Voters responded by electing Herbst to join them on the dais. The point is simple: this has been a bad deal from the beginning. And when bad deals aren’t promptly terminated, when ineffective commissioners hesitate to act even when the law and facts allow it, they don’t fix themselves. They get worse.

Meet the Mystery Financier

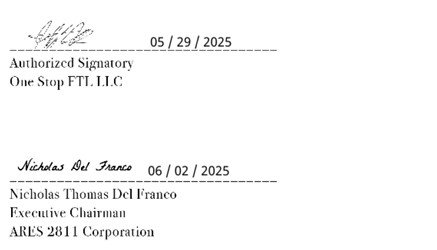

When we first uncovered the Ares 2811 Corp. letter, the most suspicious detail was its signature — simply “Management,” with no individual name, no contact information, and no accountability. Even more troubling, the letter misspelled the name of the project’s main contact.

Thanks to public records and investigative follow-up, we now know why.

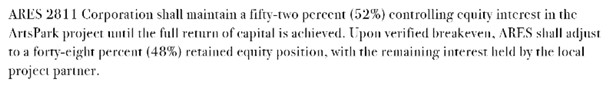

A newly disclosed document, the “Final Development Agreement,” dated May 29, 2025, does have a name and reveals that Nicholas Thomas DelFranco is the man behind Ares 2811 Corp.

And, pursuant to the same agreement, Ares 2811 Corp. will hold a controlling 52% interest in the entire project.

The Final Development Agreement claims that “All funds required to finance this project shall be sourced and deployed through ARES [2811 Corp]’s institutional funding channels.” With $58M to be deployed in year one, $79M in year two, and the remaining $55M as a credit reserve or operational facility.

But, Who is Nicholas Thomas DelFranco?

DelFranco maintains two nearly identical websites—nicholasthomasdelfranco.com and delfranconicholas.com— where he calls himself a “a successful Business Entrepreneur who has founded many different companies in a variety of fields.” Click through his bio and you’ll find page after page of vague praise, no actual names of companies he’s started, and every article authored by himself with source links to other sites with more posts he’s drafted about himself. It’s a hall of mirrors—not a resume.

A Trail of Lawsuits from Coast to Coast

His past includes multiple lawsuits alleging investor fraud, bounced checks, and vanishing inventory, with complaints filed from New Jersey to California. Three separate posts on RipoffReport.com tell a story of a man allegedly using aliases, operating shady online storefronts, and conning investors with promises that evaporate faster than his product lines.

In a 2016 lawsuit filed in California, a businessman named Harry Berkowitz accused DelFranco of orchestrating a brazen fraud involving a cannabis grow operation. After personally soliciting a $63,250 deposit to supply hydroponics equipment for a Denver facility, DelFranco allegedly delivered just four pumps valued at a few hundred dollars and then disappeared with the cash.

In 2020, in a separate California lawsuit, entrepreneur David Wise alleges that Nicholas and his father Thomas DelFranco engaged in a fraudulent scheme involving the sale and delivery of over $3.8 million in farm supplies intended for a hemp cultivation venture. According to the complaint, DelFranco repeatedly misrepresented his intent to pay and even issued a check for $42,035 that was returned for insufficient funds. Wise asserts that only a fraction of the promised crop was planted (70 of the agreed upon 1000 acres) and that Nicholas and his father failed to return the unused inventory. The complaint seeks damages exceeding $3.7 million, and alleges causes of action for fraud and conversion, describing a pattern of deception, broken promises, and personal enrichment at Wise’s expense. Another investor, Trevor Hill sued for the same incident not long after.

The following is just a sample of the lawsuits filed against him in Orange County, California alone…

Also in 2020, he was sued in a lawsuit filed in Oklahoma County alleging he took nearly 630 pounds, approximately 21 million seeds, of a marijuana strain known as “Trump 1” without paying the agreed $3.68 million purchase price. According to the complaint, the seeds were delivered by Oklahoma-based 4th Dimension HC to DelFranco, who then flew them to Colorado and never paid for them. The lawsuit alleges fraud, theft, misrepresentation, and breach of contract.

In 2022, he was sued by his landlord for eviction for failing to pay his rent. The plaintiff alleges that Nicholas Thomas DelFranco and his associate entered into a lease agreement for a luxury residence in Irvine, California, agreeing to pay $17,000 per month. Despite this, they allegedly failed to pay two months of rent totaling $34,000 and refused to vacate the premises after receiving a three-day notice to pay or quit.

It seems unlikely someone with his history of litigation could pass a commitment committee for any credible institutional investor in order to be able to borrow a hundred million dollars.

Catch Him If You Can

Much like a real-life Catch Me If You Can, Nicholas DelFranco has zigzagged across the country, leaving a trail of lawsuits in his wake from New Jersey to Oklahoma to California. Now, somehow, he’s landed in Fort Lauderdale and will have a controlling stake in city-owned land worth tens of millions. And this is the man now slated to control the majority interest in one of Fort Lauderdale’s most controversial public-private developments. What could possibly go wrong?

And like Frank Abagnale, whose exploits inspired the film, DelFranco appears to have learned the game from his father, Thomas, who is named as a co-defendant in several of the alleged schemes. One warning posted on RipoffReport puts it bluntly: “if you know these supposed ‘Business people’ run…run as fast as you can. They will do whatever it takes to further themselves without ever doing one thing that they promised. If you are working with them or thinking or leasing or selling them property or trading or giving your money…. Do your research. Contact past landlords in Michigan or Florida. Call their previous investors, ask for anything to prove they are who they tell you they are. I wish I did.”

These are exactly the types of people drawn to cities where bad governance and lobbyist-controlled politicians create the perfect conditions for exploitation, where oversight is weak, consequences are rare, and public land is treated like a private playground.

We’re doing our homework. Unfortunately, some of our city leadership is not.

District Commissioner Steve Glassman did not respond to our request for comment. However, as recently as last month, he continued to champion this project. He insisted on giving the developer more time, more leniency, and more benefit of the doubt than any rational steward of public assets ever should. But let’s be clear: the developer failed to meet its original obligation to demonstrate financing within 90 days of signing the agreement in 2022. They failed again to show proof of financing within 30 days of the city’s formal notice of default, after the City Commission declared the project in default on May 6, 2025. And now we’ve learned of a controlling interest quietly transferred to Nicholas DelFranco, an individual never disclosed in the original proposal, raising serious questions about whether the change of control itself constitutes a separate breach of the agreement.

*Although none of the lawsuits we reviewed resulted in a judicial finding of wrongdoing, the consistent pattern of allegations, including bounced checks and misrepresentations in business dealings, raises serious questions about DelFranco’s business practices.

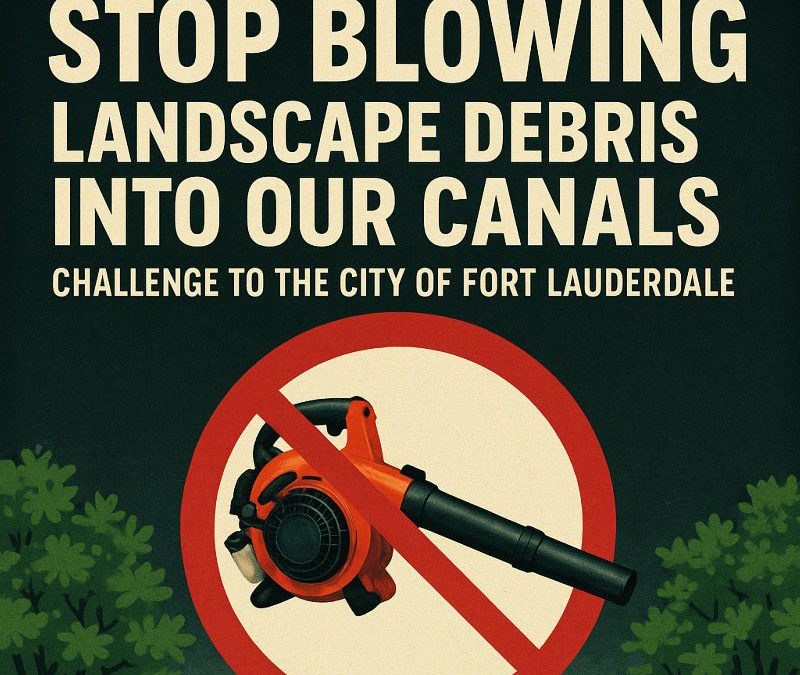

Enough Excuses: It’s Time to Save Our Waterways

I recently saw residents calling on the City to take action on something that might seem small — yard clippings. But it matters.

Fort Lauderdale loves to call itself the “Venice of America.” But if we’re honest, that title is hanging by a thread. Fort Lauderdale’s unique character, shaped by its scenic waterways, marine culture, and status as a world-class boating destination, is slipping away under the weight of political negligence, overdevelopment, and unchecked pollution.

The water is murky. Oxygen levels are crashing. Marine life is disappearing. And instead of urgency from our City Commission, we get talking points and task forces. Meanwhile, canals fill with algae, fish float belly-up, and raw sewage, continues to pour into our waterways after every major rain or infrastructure failure. Actual human waste.

Let’s be clear: this didn’t start yesterday. And it didn’t start with the headlines about 211 million gallons of sewage spewing into the streets and canals between 2019 and 2020.

We’ve been warning about this for years.

A Family Legacy of Advocacy and Frustration

In 2017-2018, my mother, former Commissioner Charlotte Rodstrom, ran a campaign focused almost entirely on controlling overdevelopment and fixing the city’s collapsing infrastructure. She talked about failing pipes, delayed maintenance, sewage backups, how some commissioners supported diverting infrastructure funding for years, and the complete lack of oversight in how this city was managing one if its most essential systems. At the time, many people didn’t want to hear it. It wasn’t flashy. It wasn’t politically convenient, and, unfortunately, it wasn’t a winning election platform.

But she was right.

And we’ve continued talking about it as the issue continued to compound and the problems worsened. It didn’t take a crystal ball to see where this was going. It just took paying attention.

Back then, most people didn’t have their wake-up call yet. That came years later, when the worst spills in city history brought national attention including a state issued environmental protection consent order that forced everyone to confront what we already knew: Fort Lauderdale’s infrastructure and waterways were in crisis.

The volume of sewage water and the damage caused by a single break are enormous. Whether it is 211 million gallons or just one pipe leaking into our storm drains for a few hours or days, the impact is staggering. And that brings us to one of the biggest challenges in this conversation — most people don’t understand volume.

We Don’t Understand Volume

Volume applies to both the pollution being added and the sheer scale of the water we’re trying to clean. Volume is hard for humans to understand. It’s not that we’re unintelligent, it’s that our brains aren’t wired to intuitively grasp massive scale. We can visualize a bucket, maybe a pool. But ask someone to picture a million gallons or billions of gallons? That’s abstract. That’s where it gets lost.

I’ve been keeping saltwater tanks most of my life. For the last eight years, I’ve been the lead moderator of a community of 140,000 people, which includes marine biologists, aquarists, conservationists, and people who really know what it takes to maintain healthy water. I’ve gone to conventions, forums, and lectures around the country for almost two decades. It sounds silly, but check us out on /r/reeftank on Reddit, it’s a community of dedicated salt water fish tank keepers who care about marine husbandry and water quality. We’ve been addressing issues the city is now confronting since the beginning of our hobby. None of the solutions you hear about regarding cleaning up our waterways are new or novel, we’ve been successfully implementing them for decades in my hobby.

In a reef tank, every piece of waste has to be accounted for. You overfeed? The tank crashes. You skip a water change? Algae takes over. You want clean water? Then you need a filtration system — protein skimmers, carbon reactors, mangroves, and other biological or chemical filters — and you need to keep it running constantly. Everything that goes in stays in (in some form or another) unless you actively remove it. There are no shortcuts. Salt water fish tanks are notoriously difficult to keep for those that don’t understand these principles.

In this world, we know something that Fort Lauderdale’s leadership still hasn’t grasped: you can’t ignore the input and expect export to save you.

Now, I have three mangrove trees growing in my living room fish tank. They are all several years old and the average person would have no idea they are even trees. Mangroves grow slowly. Red mangroves can take 5 to 10 years just to reach a few feet in height, and decades to develop the kind of root systems that make a real ecological impact. They are part of a long-term recovery, but they are not a quick fix for active pollution. That said, I believe in their power. They export nutrients naturally, bind sediment, and help stabilize ecosystems. I fully support mangrove planting projects in Fort Lauderdale. I’d love to see Las Olas Blvd, where I grew up, lined with them. Likewise, I think it would be beautiful to reintroduce mangroves to the triangle and am glad we are seeing mangrove planting at George English park.

Featuring: Nine Colorado Sunburst Anemones, three mangrove trees (top)

Water Quality? Failing. Leadership? Also Failing

Independent water quality tests confirm what residents already know. Nitrogen and phosphorus levels are off the charts. Fecal coliform counts are routinely high. Fish kills are no longer shocking, they’re expected.

Between late 2019 and early 2020, over 211 million gallons (equivalent to the Gulf Oil Spill) of raw sewage were dumped into our canals due to broken pipes and failed infrastructure. Outrage followed. Statements were made. Ribbon cuttings ensued falsely claiming the waterways were cleaned up. Promises issued. But on the ground, very little has changed. The pipe’s continue to break and manhole covers still overflow with raw sewage right into our storm drains and into our waterways. A new force main was installed but many of the pipes in our city are still decades old and well beyond their useful life. We don’t even know how old many of the pipes are.

I saw something a few days ago out on the water that should’ve made me happy, three dolphin swimming together in the Intracoastal. I’d never seen that before. I’ve seen dolphins before, sometimes one, maybe two, but never three swimming together, at least not in the Fort Lauderdale Intracoastal. It was beautiful. For a second, I felt lucky. Then it hit me: they were probably lost. The water is too polluted. They didn’t belong there. No more than a goldfish belongs in a gasoline tank. And maybe that’s the most honest reflection of what we’ve done to our waterways; even the wildlife doesn’t know where to go anymore. I hope they made it back to the ocean.

A New Title, a Real Opportunity

The City recently created a position: Chief Waterway Officer. It was a promising move, a recognition that someone needed to be directly accountable for the condition of our canals. The job was given to Marco Aguilera, a longtime City employee with experience in enforcement and municipal operations.

It’s fair to say his appointment caught some in the boating and environmental community off guard. Aguilera doesn’t come from a marine science background, nor does he have direct experience in conservation, sectors that play a major role in Fort Lauderdale’s economy and identity.

That said, this is still an opportunity. Aguilera now has a platform to make meaningful change, and if he takes it seriously, he can earn the trust of a community that’s desperate for action.

Fort Lauderdale’s Water Still Stagnates

Some people try to argue: “Well, a city isn’t a fish tank. It’s open water. Everything gets flushed out daily.” No, that’s not how this works.

Fort Lauderdale may not be a sealed system like a reef tank, but the movement of water in our canals is far slower and more contained than people think. The tides come and go, sure, but there’s limited flow.

Years ago, Buddy Sherman, longtime owner of Southport Raw Bar, once told me, only half-joking (I think), that when he died, he wanted his ashes spread in the water behind the Southport. Because, as he put it, “I know I’ll never go anywhere.”

That comment stuck with me. He was talking about legacy, but unintentionally, he explained exactly why the water never gets better.

The pollution we add stays. It settles into the sediment. It gets stuck. It feeds algae. It suffocates fish. And unless we get serious about stopping the input, nothing we do on the export side will ever be enough.

Not even mangroves. Not even skimmers the size of trucks. Not even hundreds of oysters hanging behind your dock. Not tons of biochar. Not even living sea walls. Not even prayer.

Planting mangroves is fantastic. And I am by no means trying to discourage those pushing export mechanisms. Everything matters and everything has an impact. Projects that restore oysters, deploy biochar, and reintroduce native vegetation all play a role in long-term recovery. But if mangroves are planted next to a pipe leaking fecal water, or downstream from a storm drain packed with lawn chemicals, their impact will be minimal to non-existent. The first step is cutting off the source, stopping the bleeding. I am simply calling on the City to get serious about addressing the root causes of these problems rather than expecting community-led solutions to clean up the City’s mess.

None of it will matter unless we fix the pollution.

That means:

- Fix the damn pipes (we are making progress but it has been painfully slow).

- Stop blowing yard waste and trash into the storm drains.

- Install catch screens.

- Clean the drains regularly.

- Hold contractors and developers accountable for construction run-off.

- Enforce anti-dumping rules.

- Use the money from development to protect what’s left.

This is a scale problem, a leadership problem, and a willpower problem. And it won’t be solved with pretty renderings or greenwashed press releases. It’s going to take work — real, boring, regulatory work — and a commitment to fixing what flows in.

We don’t need a rebranding campaign. We need working infrastructure.

We don’t need buzzwords. We need clean water.

We don’t need another press release. We need pipes that don’t explode under our feet and then pollute into our waterways.

The City has the money. It has the engineers. It has the data. What it lacks is the political will to act.

A Simple First Step & Shared Responsibility

If Fort Lauderdale is going to be this slow to fix its infrastructure, then the least we can do, right now, is stop making things worse.

Let’s start with a basic, common-sense ask: City employees and contractors should stop blowing debris, especially biological waste, into our storm drains. That includes leaves, grass clippings, trash, dog feces, and any other organic matter that becomes nutrient pollution the moment it hits the water.

Blowing yard debris is a serious environmental and infrastructure problem. First, those clippings break down and release excess nutrients into the water, fueling algal blooms and choking marine life. Just as critically, they clog our stormwater infrastructure, block check valves, and slow drainage. Over time, this causes backups that contribute to street flooding and reduce the system’s ability to handle even normal rainfall. And in a city facing rising sea levels and a growing threat of tidal and rain-driven flooding, seemingly small practices like this matter more than ever.

Is this a drop in the bucket? Absolutely. But it is an easy and practical step that can be done with relative ease.

And let’s take it a step further. If you have a landscaper, tell them to rake and bag. If you do your own yard work, put the waste in your green bin, don’t blow it down the street. That debris ends up in the same water you boat in, fish in, live near, and rely on.

This is a simple first step. It shows leadership. And it proves that we actually care about the city we claim to love.

Credit where it’s due: much of this conversation, especially around blowing pollutants into drains, has been amplified by @FixFTL on X (formerly Twitter) and people like Jeff Maggio. Give them a follow. They’re doing the work.

Let’s stop blowing it.

May 6th Conference Recap: One Stop Chaos, Lobbyist Loopholes, and the Toothaker Show

Enjoy our editorials? Check out our new podcast above!

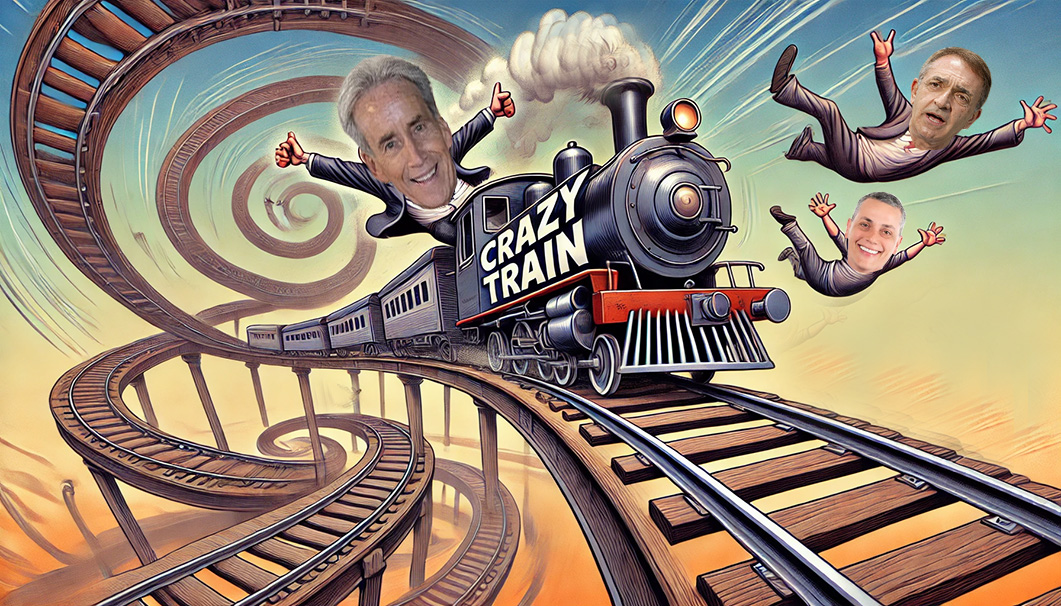

Tuesday’s Commission conference meeting was supposed to be a routine update on city business. What it turned into was something else entirely — a chaotic and revealing look at how Fort Lauderdale’s most powerful lobbyist continues to shape policy and bend the system to serve a narrow few. If anyone needed more evidence that this city operates on insider access and developer privilege, this meeting provided it in full color.

Let’s start where we left off: One Stop Shop. If you read our last editorial, you could have used it as a play-by-play program for this week’s conference meeting. Every issue we predicted showed up, from missing financing documents to special treatment to the city’s chronic inability to hold developers accountable. This boondoggle of a project, greenlit over three years ago, has produced zero construction, zero permits, and zero rent on 3.3 acres of prime public land. But what it has generated is a mountain of excuses. On Tuesday, the pile got higher.

Developer Jeffrey John arrived with a mystery man whose role was never clearly defined. Together, they attempted to explain the project’s financing. They dropped a company name, then corrected it. Was it BGC London? BCG London? They weren’t even sure if they could say it out loud. A member of the public later pointed out that the firm’s website identifies it as a broker, not a lender. So who exactly is putting up the $100+ million they claim to have secured?

John then claimed that he, “ARES,” and the financial group had all signed some kind of agreement. If “ARES” refers to the same ARES 2811 CORP. we discussed last week, the one tied to a suburban home in New York and no digital presence, that should alarm everyone. But again, no documentation was submitted, nor was it submitted later that night.

One Stop, No Progress, Same Protection

So how does this continue? Well, start with Stephanie Toothaker, who represents One Stop Shop and was seated next to the developer. Then look at who still insists on defending this project: Commissioner Steve Glassman, who said he sees no reason to terminate the agreement. Glassman was one of the original cheerleaders for this deal. That hasn’t changed, even as it spirals further into absurdity.

Mayor Dean Trantalis seemed skeptical — as did Commissioner Ben Sorensen, breaking with Glassman for the first significant time in recent memory. Could it be that Trantalis and Sorensen are finally hopping off Glassman’s crazy train? If so, it’s about time. Because the only thing more bizarre than this project’s complete lack of documentation was the wild defense of it by Commissioner Glassman. Thankfully, Commissioners Herbst and Pittman weren’t buying the excuses either. Herbst, a finance and accounting professional, flatly stated that he’s never seen anything like it. It took that level of pressure just to get the Commission to send a formal notice of breach, giving the developer 30 days to cure. Which sounds serious, until you remember that these financing commitments were due within 90 days of the contract being executed. The contract was executed three years ago.

Why did staff let this slide for so long? Why has the Commission been asleep at the wheel? And more importantly, why does Toothaker’s client continue to receive this kind of protection when any other vendor would’ve been terminated years ago?

Let’s also talk about what Glassman actually said. In one of the more absurd moments of the meeting, he warned that if the One Stop Shop project fails, we’ll end up with “massive towers” on the property instead. Let’s be very clear: this is public land. There will be no massive towers on this site unless the City Commission gives the land away and approves such a project. The only people who can make that happen are the five commissioners sitting on the dais, and last time we checked, Glassman is one of them. What kind of commissioner threatens the public with an outcome like that as justification for keeping a questionably financed deal alive after three years of no progress?

It didn’t stop with One Stop Shop.

The Lobbyist Ban That Wasn’t

The Commission also discussed a proposed ordinance that would ban lobbyists from sitting on city boards. Seems straightforward enough, unless, of course, you’re trying to protect a specific person. Mayor Trantalis immediately suggested the ban shouldn’t apply to boards non-advisory boards a/k/a those with real authority, like the Downtown Development Authority (“DDA”) or the Performing Arts Center Authority (“PACA”). That’s backwards. As Commissioner Herbst pointed out, advisory boards are already ignored. The real concern is the boards that handle budgets, shape policy, and influence development, like the DDA.

So why did the Mayor suggest carving out those boards? Maybe because Stephanie Toothaker is Vice-Chair of the DDA and is in line to become Chair. She’s the only lobbyist on the board. The DDA has enormous sway over the future of Fort Lauderdale’s growth and development. Toothaker’s position there isn’t ceremonial. It’s power, real power. And Trantalis and Glassman appear far more concerned with protecting her than with protecting the public from undue influence.

And here’s the kicker. The ordinance, as drafted, would not have excluded either Barbara Stern or myself, despite Glassman’s public complaints about their appointments to the Planning & Zoning Board. So what exactly was his concern? It wasn’t about consistency. It wasn’t about ethics. It was about control.

Tuesday’s meeting showed how far this city is willing to bend when the right lobbyist is in the room. It showed who still gets a pass when rules are broken, deadlines are missed, and the public is lied to. And it showed how fragile our systems really are when they’re run on private influence instead of public accountability.

Fort Lauderdale deserves better than a government that works for one person.

It’s Time to Kill the One Stop Shop Deal

On Tuesday May 6, 2025, the Fort Lauderdale City Commission will be reviewing the status of the infamous One Stop Shop project as part of their conference agenda. Let’s be blunt: it’s time to kill this deal.

Over three years ago, on March 15, 2022, the Commission approved a Comprehensive Agreement with One Stop FTL, LLC for the development of a so-called “Arts Park” on 3.3 acres of prime, city-owned downtown real estate. What’s happened since? Absolutely nothing. Not one submittal to the Development Review Committee. Not a single building permit application. The site sits idle, locked up for private development while our community pleads for more park space and accessible public land.

The developer is paying nothing for the land, literally zero dollars, until one year after construction is completed. And the most important piece? There are no deadlines in the agreement for when construction must begin. In fact, per the agreement, the project only needs to be completed within three years of pulling a building permit. And guess what? No permit, or deadline to pull one, means the clock hasn’t even started ticking.

Worse still, this is another one of the City’s favored “license” deals rather than a “lease” allowing the developer to avoid certain processes and requirements, like with Snyder Park and other development projects. You know, the kind of transparency most taxpayers expect when public land is involved. And lets be clear, functionally there is almost no difference between a lease and how the City has structured these licenses.

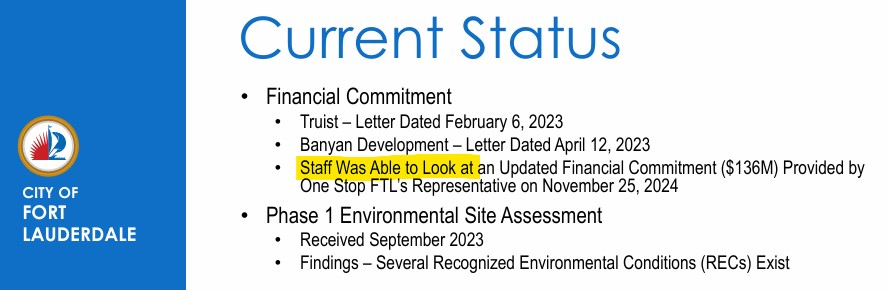

The City Commission will be reviewing a presentation prepared by staff, but let’s not pretend it tells the whole story. For example, it states staff “was able to look at” an updated financial commitment from November 25, 2024. But that’s not the same as receiving it. According to sources familiar with the matter, staff viewed the documents on the Developer’s IPad—but were not provided copies, raising concerns about whether this was done to avoid creating a formal public record. We deserve formal, verifiable documents that are accessible to the public. In the sunshine. As the law prescribes. You can download the City Staff Presentation here.

The Investor Behind the One Stop Shop?

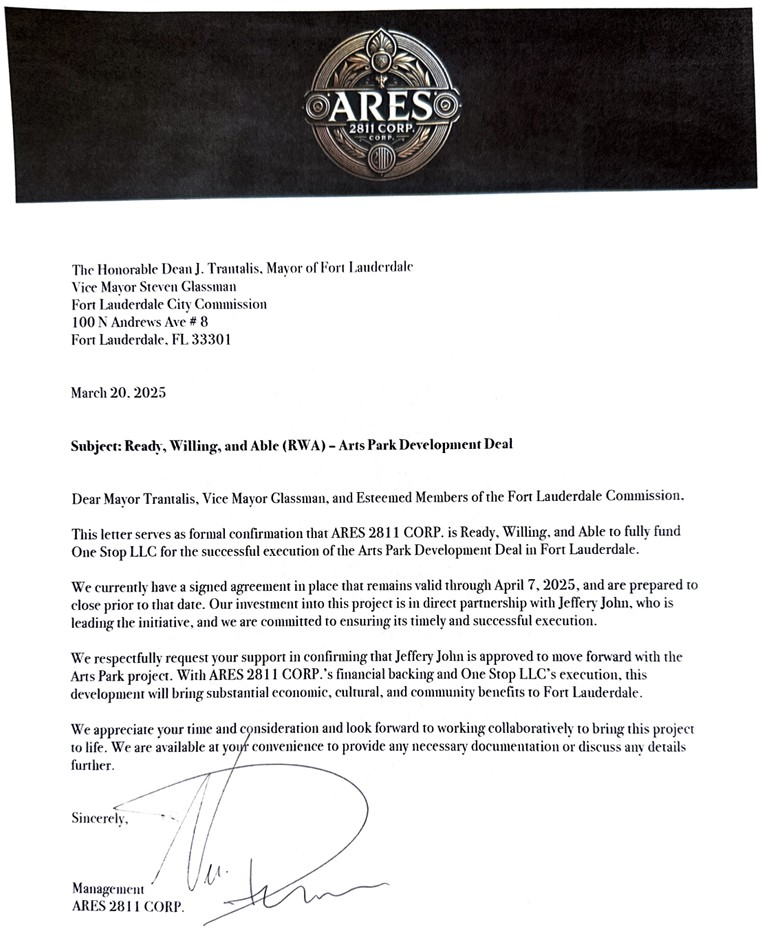

Even more baffling is the omission of the more recent March 20, 2025 “Ready, Willing and Able” letter from a supposed investor, ARES 2811 CORP stating they are ready to “fully fund One Stop, LLC.” Unlike the other letter, the City actually has this one, we received it after reviewing a public records request, but it’s nowhere to be found in the presentation materials. Why?

Probably because it raises more questions than it clears up. The letter is:

- Not addressed from any named individual.

- Lacks a return address, phone number, or website.

- Fails to mention any specific financial capability.

- References a partnership with Jeffery John (the developer), yet no supporting documentation accompanies it.

Typical proof of funds or financing letters come from a bank, investment firm, or recognized lender and include formal language like: “[Entity] or its affiliated accounts has available cash balances in excess of [$X],” or “We are prepared to extend financing in the amount of [$X] to [Project or Borrower].” They’re usually on official letterhead, signed with a printed name and title, and easily verifiable.

In some cases, a developer may also provide bank statements, corporate financials, or tax returns to demonstrate their financial capacity or ability to raise funds, anything that actually substantiates they have the means to follow through. This letter, by contrast, contains no contact information, no company credentials, and while it is signed, there’s no printed name or formal signature block identifying who signed it. That’s not how serious financing commitments are documented. It’s not standard—and it’s a red flag that deserves scrutiny, not omission from the public materials presented to the City Commission.

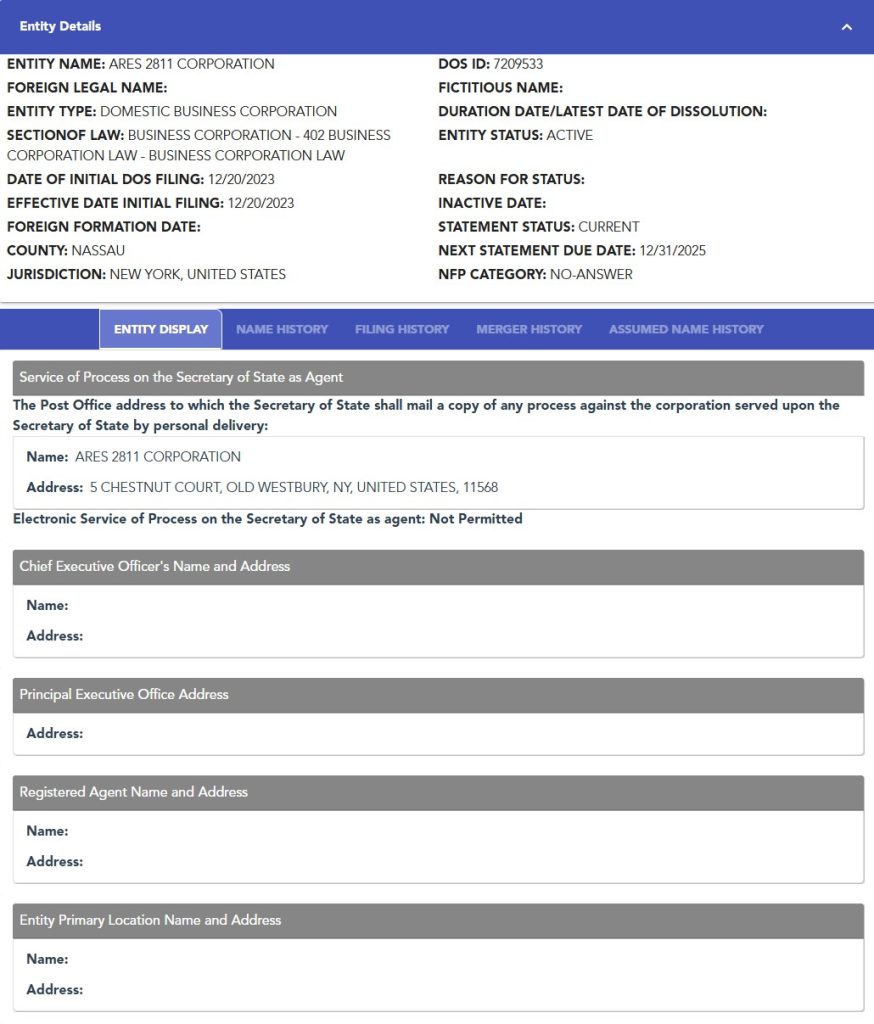

A little research reveals that ARES 2811 CORP. is a New York corporation formed in December 2023. The listed address for the corporation traces back to a single-family home in Nassau County, NY—not exactly what one would expect for a major development financier. The NY Department of State database doesn’t list any officers or directors and a quick Google search reveals no digital footprint for the company. Searching the two individual owners of the property doesn’t get you very far either.

Is ARES 2811 Corp the company that provided the “updated financial commitment” the public can’t review because it was never formally submitted to the city? If not, who did? And where does ARES 2811 fit into the mix? If this is the developer’s updated proof of funding, we’re in deeper trouble than we thought.

So here’s the question: Why was this letter not included in the presentation? The public shouldn’t have to file public records requests to see documents related to a $100 million development deal on public land worth at least $35 million. If this letter is supposed to represent financial capacity, why wasn’t it included in City Staff’s update to the Commission? Is staff choosing not to include it? Or were they directed not to by someone else? Either way, this kind of selective disclosure undermines public trust and raises serious concerns about what else is being kept out of the public eye.

The Bloc Strikes Again

And let’s be clear who voted for this contract three years ago, despite warning after warning, even then, about how bad this deal was. None other than The Bloc—Mayor Dean Trantalis, Commissioner Steve Glassman, and Commissioner Ben Sorensen—who have become fan favorites for criticism both on this website and across the city. This was their vision. Their vote. Their responsibility. And now, three years later, they have nothing to show for it.

Time to Walk Away

Commissioner Glassman was recently quoted as saying “I recently met with the development team and have been assured that all systems are go,” he said. “I am not in favor of terminating the agreement.” No surprise considering he was one of the original fans of pushing this project.

Let’s be real: this isn’t just a stalled project—it was a bad deal from day one that’s only getting worse with time. We’ve been patient. We’ve been generous. But now, we’re being played. Actually, we were always being played.

The City Commission must do the right thing and explore avenues to terminate the One Stop Shop deal. If other members of The Bloc want a shot at redemption they can start by figuring out how to tear up this deal. This should be a public park, maybe one that’s owned by and managed by our city for the benefit of its residents rather than private development interests. Heck, the City Commission can even use some of that $200 Million Parks Bond we voted for over 5 years ago that they seem to have so much trouble spending.

Why I Started FTL Politics — And Why I’m Not Stopping

Now that I’ve decided to formally step forward, I want to be crystal clear:

I was never hiding.

I started this editorial site because I was frustrated — angry at the direction of our city and the blatant disregard for our residents that emanates from some of our City Commissioners. This wasn’t about secrecy. It was a needed pressure valve. It was about creating a platform to speak truthfully without the constant threat of retaliation hanging over my head. It was about making sure the message was louder than the messenger.

I left breadcrumbs everywhere: the strong opinions I’ve held for years, the insider knowledge, references to my alma mater’s city, heck even the website hosting tied to my other businesses. Anyone seriously investigating could have figured it out. In fact, I hoped a few people would. But I wasn’t going to broadcast my name with a neon sign before I had the chance to learn what this passion project could be or before I knew for sure that I was all in with it.

The truth is, I’ve felt more emboldened with every post, not because of what I’ve written, but because of how many of you have responded. The support, the shared stories, the “keep going” messages, they’ve made it clear that this project tapped into something real.

When I posted the first editorial, I had no idea what kind of reaction to expect — whether five people would read it or five hundred (our unique user count almost exceeds that daily). I also didn’t know if I would even want to keep it going after a few posts. But the overwhelming support, the engagement, and the sense of community has strengthened my resolve beyond anything I imagined. It was incredibly telling after just the first post, and the momentum has only grown. As someone who has written professionally for years, it’s been amazing to finally find my voice as a Fort Lauderdale resident, not just as a lawyer or someone supporting a candidate as I have in the past.

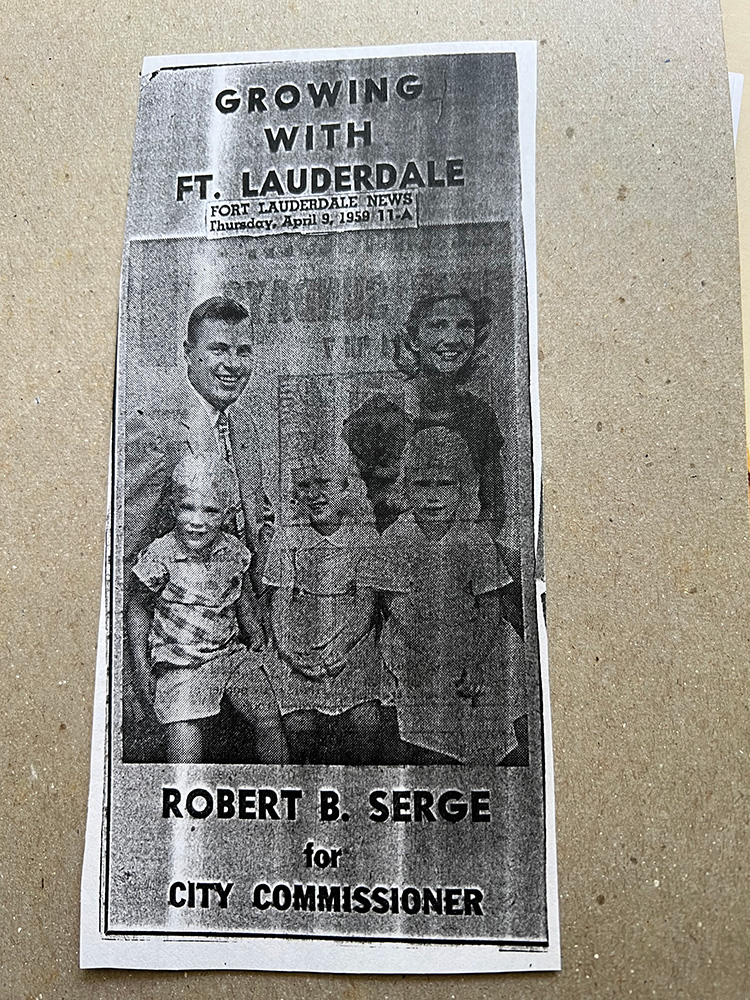

Public service runs in my blood. My grandfather, Robert Serge, ran for the Fort Lauderdale City Commission in 1959. My father, John Rodstrom Jr., served on the Fort Lauderdale City Commission in the 80s, was appointed Mayor of Sunrise by the Governor to clean up after a corruption scandal, and later served as a Broward County Commissioner for the first 20 years of my life. My mother, Charlotte Rodstrom, served two terms as a Fort Lauderdale City Commissioner and twice as Vice Mayor.

Bottom: Alex Serge, Charlotte Rodstrom (my mother), Sara Turse

That background taught me that holding public office isn’t about titles or vanity projects. It’s about stewardship. It’s about acting as a fiduciary for the voters who trust you with their city — something too many of our current leaders have forgotten.

That’s why I started this website.

While I’ve written most of the content, this has never been a solo act. There are others directly involved who wish to stay anonymous. Importantly, FTL POLITICS is a collective voice of residents who care — people who provide story ideas, sources, outlines, and encouragement every step of the way. Together, we’re trying to shine a light where others have conveniently looked away. Contributors include close friends who have been part of my journey for a long time. They’re neighborhood activists, water conservationists, homeless advocates, friends, and everyday residents who are simply too stubborn to pack up and leave when the going gets tough, like myself.

And just to be clear, we are not a news outlet. This is a blog. It’s editorial, it’s opinionated, and yes, it can get personal. While we may “break news” from time to time, every post is written as a piece of commentary. This is my outlet to express my perspective on what’s happening in our city.

But I don’t expect you to take my word for it blindly. I believe strongly in backing up my opinions with facts, records, and real sourcing as I always have when I post anything online. My budget editorial, for example, links to over 17 separate sources. I’m trying to inform, to explain, and maybe, if I’m doing it well enough, to help you understand why I feel the way I do. Maybe you’ll even come to feel the same way. Fort Lauderdale has real problems, and we need to stop pretending otherwise. Being critical of the people responsible isn’t negativity. It’s accountability. And frankly, we need a lot more of it.

Now that my name is out there, the only thing that changes is the signature at the bottom (or top). The mission remains the same: tell the stories others won’t, expose the spin, challenge the bs, and fight for Fort Lauderdale.

Thanks for reading, sharing, and caring. I hope you’ll continue to follow along.

It’s going to be quite the ride.

John Ethan Rodstrom III

Founder & Chief Editor of FTL POLTICS

Goodbye Basketball, Hello Pickleball

On January 9, 2024, the Fort Lauderdale City Commission did what they do best: give away another piece of our city.

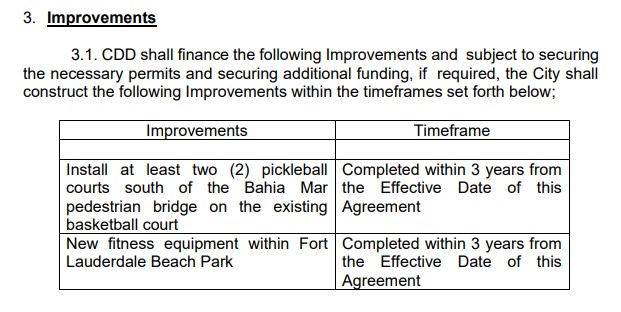

In a vote that centered around the conveyance of “air rights” for the Bahia Mar project — air rights, mind you, above public land — the Commission also approved an Interlocal Agreement. In it, the Bahia Mar Community Development District promised to add two public pickleball courts “south of the pedestrian bridge on the existing basketball court.”

There’s just one problem.

There are no basketball courts south of the pedestrian bridge. The only public basketball courts in the area are north of the pedestrian bridge, east of A1A, on the beach, in Fort Lauderdale Beach Park. Courts that, for decades, have served residents and tourists alike. Courts that offer a place for pickup games, community events, and yes, a space for local kids who don’t have memberships at the fancy yacht club or private condos.

AND BAHIA MAR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT DISTRICT

And now, those are the courts will be torn up to make way for pickleball.

No public debate since no one knew this was the intention of the Interlocal Agreement. No real notice. Just a quiet sign going up last weekend: “COMING SOON BASKETBALL COURT CONVERSION TO PICKLEBALL”

A City Sold Out One Court, One Park, One Neighborhood at a Time

The Bahia Mar deal was already controversial. A historic waterfront site owned by the public turned into a playground for luxury towers with a few token nods to public use thrown in.

In reality? It’s the slow gentrification of the beach, one that pushes working-class residents and community amenities further and further out. It’s hard to ignore the racial and socio-economic undertones, given that basketball courts have historically been more inclusive spaces, while pickleball — rightly or wrongly — has developed a reputation as a sport geared toward affluent, older, and overwhelmingly white demographics.

The removal of public basketball courts in favor of pickleball, particularly on the beach, sends a message, intended or not.

It tells you who this city is being remade for.

It tells you whose recreational needs matter.

And it tells you who is being pushed to the sidelines.

Pickleball, Pickleball Everywhere

Fort Lauderdale’s current Commission, particularly Commissioner Steve Glassman of District 2, has been infatuated with pickleball. It’s been pushed at almost every park in the city and has been talked about at nearly every open space left in the city.

No one’s saying pickleball doesn’t deserve facilities. It’s a fast-growing, popular sport, and there’s plenty of demand. But why does “adding pickleball” always seem to mean taking away something else?

Why not build new courts instead of repurposing the only public basketball courts we have on the beach?

Why not invest in real multi-use spaces that serve different demographics, not just whichever group is trending?

Why was there no real public discussion before handing over these courts?

I guess they figure the future owners of the St. Regis would rather serve pickleballs than see local kids shooting hoops.

Untitled…

Not everything fits neatly into a category. Neither do we.

Fort Lauderdale on the Brink: Mismanaged, Maxed Out, and Unprepared

If Fort Lauderdale’s budget were a household, it would be the kind of place where the lights are on thanks to maxed-out credit cards, the roof leaks because repairs were put off, and the furniture has been pawned for a quick fix. That’s what The Bloc, Mayor Dean Trantalis, Commissioner Ben Sorensen, and Commissioner Steve Glassman have done to our city—pawned off our most valuable lands and assets to developers and private interests for pennies on the dollar, all to fund short-term vanity and record-breaking campaign accounts.

And now? The bill is coming due.

At a recent budget workshop, the City’s financial advisor laid out a dire scenario: a looming $107 million budget deficit and emergency reserves depleted within a few years. For too long, commissioners have clung to the fantasy that growth pays for itself. But rising home values, driven by a regional real estate boom rather than local leadership, only masked the truth. The City’s operating costs exploded alongside that growth, bloated by political pet projects, questionable raises, new hires, and unsustainable new programs.

The police station? Ballooned from $100M to over $150M, with serious structural concerns. City Hall? Left to crumble and now we may need to float another bond for a fancy new building, because this commission wants its name on something new.

Some of these same commissioners doubled their salaries and enjoy car allowances generous enough to support Bentleys. All while basic services, like keeping up with police and fire staffing, lag behind.

The One Stop Shell Game

And let’s not forget the disaster that is the One Stop Shop — another Stephanie Toothaker deal — passed more than three years ago and still not a shovel in the ground. The City collects zero rent until construction is completed. Even worse, the developer has never even pulled a building permit, because the clock for the three-year construction deadline doesn’t start ticking until they do. No construction deadline. No guaranteed timeline. No revenue. Just promises.

“The business plan was deeply flawed, which is why it has yet to be built,” said Commissioner John Herbst, who it is believed was fired as the City Auditor at the time over his criticism of the deal.

That same parcel — 3.3 acres of prime, city-owned land in the heart of downtown, steps from our now-demolished City Hall — could have been used to build a new City Hall or at least finance one. Instead, it was handed over for nothing, licensed away on buzzwords like “cultural arts park” for a food hall that will likely never materialize. And let’s be honest—one of three things is likely to happen: the original developer flips the deal to another buyer and what gets built bears little resemblance to what was promised; nothing happens for the foreseeable future as the land sits idle; or the City finds a way to quietly exit the deal to make room for another sweetheart arrangement with a different lobbyist-backed developer—we’ll bet on the latter.

Likewise, Bahia Mar is being redeveloped with little gain for taxpayers and the air rights were given away so that we now will have condos on public land in perpetuity.

The City That Fell in Love with Renderings

And to be clear: you can like some of these projects and still find the process reprehensible. It’s not the concept of a park upgrade, a cultural district, or a stadium that should make your skin crawl — it’s the disposition of public land, your land, for even a penny below fair market value. That’s the issue. When deals are cut with lobbyists behind closed doors, without transparency, without accountability, and without securing fair value for taxpayers, it doesn’t matter how nice the rendering looks — the public is being robbed.

Turning Water Into Gold

But let’s not forget Fort Lauderdale’s water plant, one of the City’s most critical assets, was basically handed off through a Public-Private Partnership, despite our AAA bond rating that could have secured a far better deal for ratepayers. Now, residents are staring down the barrel of water rates that may double to cover private profit margins.

While former Commissioner Ben Sorensen didn’t cast a vote on the final approval of the controversial water plant project, he had spent years championing it and pushing it forward. He didn’t get the chance to vote on the final contract because he resigned mid-term to pursue a failed run for Congress, leaving his district behind just as the most consequential decision came to a head.

His successor (and now predecessor), Warren Sturman, who was elected in a short-term special election, ultimately cast the vote in favor of the project. That vote stands as one of the more long-lasting negative effects of Sturman’s short and disjointed time in office — a term that ended when he came in third in his own re-election bid returning his seat to Sorensen.

Lessons We Refuse to Learn

Cities across the U.S.—from Coatesville, Pennsylvania, to Salem, New Jersey, and even right here in Florida—have learned the hard way what happens when you hand over public utilities to private interests. In Jacksonville, the city privatized its water system in the late 1990s, only to see rates spike and residents revolt. The backlash was so strong that Jacksonville ended up borrowing hundreds of millions of dollars to buy the system back just to try to bring rates under control.

Gainesville offers another cautionary tale. In 2009, Gainesville Regional Utilities entered into a 30-year power purchase agreement with the privately owned Gainesville Renewable Energy Center, committing to pay approximately $70 million annually, totaling over $2 billion over the contract’s duration, even if the facility wasn’t producing power. This agreement led to some of the highest utility rates in the state. In response to public outcry and financial strain, the city decided in 2017 to buy out the contract and purchase the biomass plant for $750 million of debt financing.

They Want More—and They’ll Get It from You

And if that’s not enough? City officials have floated an EMS assessment tax, because Fort Lauderdale is one of the only cities in Broward that doesn’t staff its ambulances with three-person teams. The City Attorney recently stopped that proposal in its tracks, but the appetite for new revenue remains strong.

And for the record, we fully support three-person rescue crews. We think it’s astonishing we don’t already have them. But maybe that should have been a priority instead of funding a literal award-winning propaganda—erm, I mean, “Strategic Communications Department.”

Some commissioners, most notably Glassman, are already downplaying the need for tax hikes. But the truth is, the conversation is already shifting. Bill Brown, chair of the city’s Budget Advisory Board, and one of Glassman’s chief lieutenants, said it bluntly: “At some point, they’re going to have to raise the tax rate.”

Commissioners have begun testing the waters, citing increased pension costs, expiring grants, and spiraling construction budgets. And yet no one wants to talk about cutting bloat, auditing contracts, or asking whether every trip and consultant fee is truly necessary. Instead of trimming the fat, they’re coming for your wallet.

Those developers got sweetheart deals — but now, when the bill is coming due, it’s you, the taxpayer, who’s expected to make up the difference.

Tunnels, Towers, and Tone-Deaf Leadership

It’s a cultural problem. The Bloc of Mayor Trantalis and Commissioners Glassman and Sorensen just doesn’t get it. While residents face soaring insurance, assessments, and utility bills, our elected officials are busy chasing a $1.5B tunnel, ignoring more sensible options like the bridge for the new commuter rail that the County offered to fund.

And that growth they keep promising would pay for itself? It’s only made things worse. Infrastructure continues to crumble. The city couldn’t even hire enough project managers to keep up with the money they borrowed for repair work. Traffic congestion has reached unbearable levels. Our environment is being bulldozed in every direction. And while luxury towers go up, the lack of transitional and affordable housing has pushed Fort Lauderdale’s homelessness crisis to an all-time high.

Digging Deeper into Debt

For those paying attention, the question is simple: where is the money coming from? These commissioners have been on a spending spree without checking the bank account. At this point, it’s hard to tell whether The Bloc wants to dig a tunnel — or just dig us into debt.

Clinging to a Sinking Ship: Fort Lauderdale’s $344 Million City Hall and the City Manager Fallout

The public reaction to Fort Lauderdale’s proposed new City Hall was immediate and overwhelmingly...

Why Fort Lauderdale Residents Should Be Outraged Over the One Stop Shop Fiasco