On May 6, 2025, the City Commission finally had enough. After years of empty promises and a fenced-off city owned 3.3-acre lot in the heart of Fort Lauderdale, they declared the One Stop Shop developer in default. The reason? Failure to prove financing.

Three days later, the City Attorney’s office sent a formal notice of default, giving the developer 30 days to cure. That should have been the beginning of the end for a project that’s been all smoke and no shovels since its approval in 2022.

But this is Fort Lauderdale, where accountability often gets lost in the paperwork shuffle. On August 27—110 days after the default notice—the Interim City Attorney quietly issued a “Notice of Partial Cure.” His reasoning? The developer had, in his view, provided the proper proof of financing documents.

Here’s the kicker: staff and the City Auditor’s Office strongly disagree.

A Cure Nobody Believes

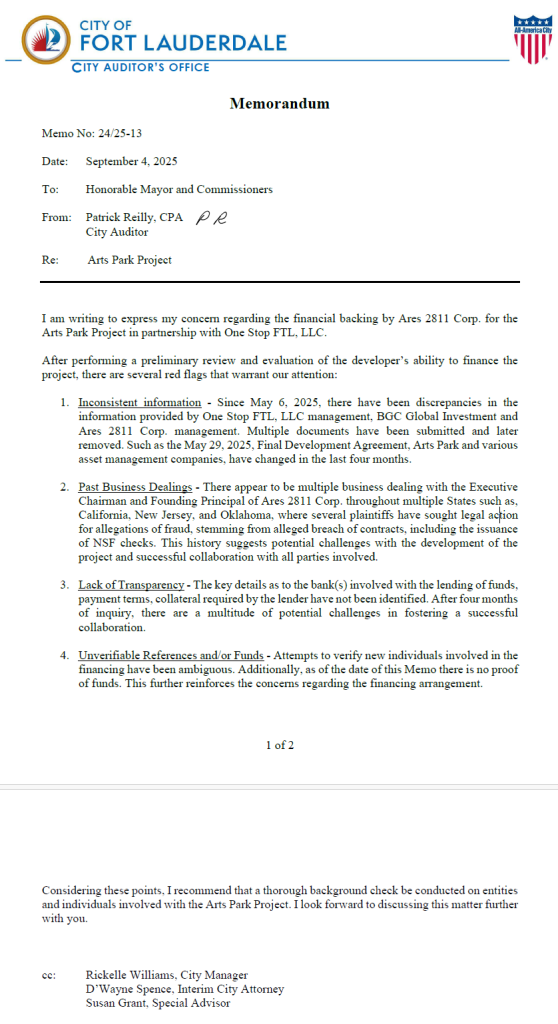

Within days, the cracks in the Interim City Attorney’s decision started to show. On September 4, City Auditor Patrick Reilly sent a memo warning of “several red flags,” including “inconsistent information,” “past business dealings,” “lack of transparency” and “unverifiable references and/or funds.” His blunt conclusion:

“As of the date of this memo there is no proof of funds. This further reinforces the concerns regarding the financing arrangement.”

The City Auditor’s September 4 memo also confirms what we reported months ago: Nicholas Thomas Del Franco, the man now slated to control a majority stake in this public land deal, comes with a troubling history. City Auditor Patrick Reilly’s review flagged Del Franco’s “multiple business dealings” in California, New Jersey, and Oklahoma, where plaintiffs have pursued legal action over allegations of fraud, breach of contract, and even bounced checks. This language mirrors the findings FTL Politics published back in May, when we detailed a dozen lawsuits filed against Del Franco across multiple states, painting what we believe to be a consistent picture of risk and unreliability (one of the best editorials we’ve done if you haven’t read it). That the city’s own auditor has now raised the same red flags makes it impossible to dismiss these concerns as speculation. The memo concludes by recommending a “thorough background check be conducted on entities and individuals involved[.]”

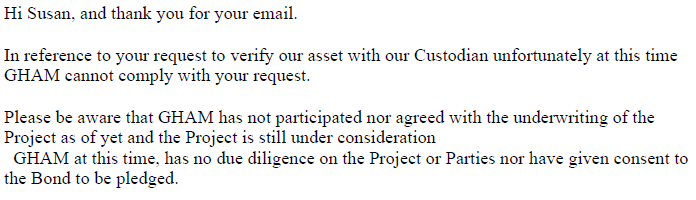

Special Advisor Susan Grant also raised alarms. In an August 27 memo, she noted that Gauntlet Holdings Asset Management (“GHAM”), one of the supposed financiers, “had not previously been identified” as part of the deal.

Less than two weeks later, Gauntlet confirmed Grant’s instincts. In a September 8 email, the firm told the City it “has not participated or agreed with the underwriting of the project as of yet, and the project is still under consideration.”

So, the Interim City Attorney issued a partial cure letter saying financing had been proven—while the City’s own staff was scrambling to verify if the financiers even really knew about the project.

The September 3 Meeting: Red Flags Everywhere

Not long after the Commission returned from its summer break, it was clear things were spiraling. Commissioner Sorensen brought up the item at the September 3 meeting with a warning:

“Mayor, I have major concerns, as I have talked to staff they have significant concerns.”

City Auditor Patrick Reilly was more direct:

“I don’t know what bank they are dealing with, I don’t know the terms, and I don’t know when that money is coming . . . The four documents we have have not satisfied me that we actually have the funding. I would like to confirm the funding.”

He revealed he even called London to speak to a man listed in financing documents, only to find that he had “no idea who Jeffrey John [the developer] was.”

Commissioner Herbst, a CPA, CFO, and former City Auditor, was floored:

“You are telling me the guy who is providing $140M in financing has no idea who he’s giving it to?” . . . “This is as bad as the first time when I asked the [the developer] who he is borrowing the money from and he didn’t even know the name of the company.”

Commissioner Beasley-Pittman said what many were thinking:

“Who does business like this? . . . Better Business Bureau, police, somebody, this is fraud.”

Glassman’s “Two Towers” Defense, The Mayor’s Breaking Point

Only one commissioner seemed unbothered: Steve Glassman, who has championed this deal from the start.

“Financing is there, they are ready to go,” Glassman said, insisting that the project was “excellent” and suggesting critics just didn’t understand the process.

But even Mayor Dean Trantalis, once a vocal supporter, had enough:

“I have been in favor of this project from day one, but it’s not happening. It’s a flim-flam. Come on, either do it or get off the pot.”

The Mayor pointed out that the developer hasn’t even provided the $250,000 good-faith payment promised in May:

“If they can’t come up with $250,000, how are they going to come up with $140 million?”

Commissioner Glassman has long defended this deal with a dire warning: if this project doesn’t happen, downtown Fort Lauderdale will get “two more high-rises with no park space.”

But this claim is a red herring. The land in question is city-owned public land. Any project on it would require full City Commission approval, just like this project did. There is no active plan, submission, or proposal for two towers on this site, and no developer could simply build there without the city’s blessing.

By framing this as a choice between a questionable deal and phantom towers, Glassman is misrepresenting the city’s options. The real choice is between giving away prime public land to a developer with unverified financing or reclaiming it for the public good.

Contracts Work Both Ways

In today’s Sun Sentinel op-ed, developer Jeff John claims the City of Fort Lauderdale is undermining its reputation by “reneging” on a signed agreement. But this narrative ignores a fundamental reality: contracts work both ways. The City Commission, as steward of public land, has not only the right but the obligation to enforce agreements, especially when they determine a developer has failed to meet clearly defined terms.

The One Stop contract was not a blank check. It included deadlines and financing requirements designed to protect taxpayers. In our opinion, those obligations have not been met. Hell, the agreement required proof of financing within 90 days of it being signed back in 2022… The project remains stalled three years later, with no verified financing (according to the City Auditor), a missing $250,000 “good faith” payment, and mounting red flags identified by city staff and the City Auditor. Enforcing those terms is not a “political agenda.” It’s basic governance.

At the very end of Jeff John’s op-ed, there’s an editor’s note: “Fort Lauderdale declined to respond to John’s assertions. The city cited a letter from John’s attorneys that raises the possibility of legal action against the city.” That’s right — after years of missed deadlines, incomplete financing proof, and a default notice, the developer is now threatening to sue Fort Lauderdale for daring to hold him accountable. Some partner.

If Fort Lauderdale were to ignore blatant breaches and continue extending lifelines, that would erode trust in the city’s leadership and send a dangerous message to future investors: rules don’t matter here.

A Pattern of Excuses

Let’s recap:

- The Commission voted for default in May.

- The Interim City Attorney quietly issued a partial cure in August, claiming financing had been proven.

- Staff and the Auditor’s Office now openly say financing has not been confirmed.

- Commissioners are being told to give the developer more time—again.

This is the same song-and-dance we’ve seen for three years: delay, excuse, repeat. The site is still fenced off. There’s still no shovel in the ground. And now there’s even more confusion about who’s really bankrolling this project.

As the Sun Sentinel wrote:

“Time to bring down the curtain on this years-long farce . . . Unless he stands in the middle of Broward Boulevard next week holding $140 million in cash, Arts Park appears dead or dying.”

Enough Slack

Why is the Interim City Attorney playing defense for a project the City Auditor openly says is full of “red flags?” Why was a partial cure issued without it being discussed at a city commission meeting and without independent confirmation of financing?

And now, the clock is ticking again. The One Stop Shop project is scheduled to be back on the agenda at tomorrow’s City Commission conference meeting at 1:30 p.m.. Residents should be watching closely (and attend if possible)—because once again, the future of this public land is on the line.

The Commission owes taxpayers an answer. Fort Lauderdale has waited long enough.

Rescind the partial cure. Terminate the agreement. Reclaim the land. Restore some integrity to city government.

Answers needed!!!!

I initially, like Comm. Sorensen, a huge supporter of this development plan. The idea of another concert venue and park that I can walk to intrigued me.

After the May 6 meeting, I soured on this plan. The developer could not give firm proof of financing after 3 years time to secure.

Time now to close this proposal and open up the site for possible future PARK development. The threat that 2 towers can fit on the site is unreal as it is city property and I see a very loud outrage if it is sold or leased (think Bahia Mar) to private development.

Tomorrow should be “interesting”.

I was at the meeting in May and sat in disbelief along with several other regular citizens while listening to the developer and his financial guy speak about the finances and respond to Commissioner Herbst’s questions.

Everything we heard relative to the source of the money was something we were all warned about at some point in our lives relatives to scams and businesses to avoid.

I understand the city may not know all the developers/players backgrounds when the P3 is submitted, but by the time contracts are signed you’d think the city would have a better handle on the developer’s source of funding.