Two years ago, Fort Lauderdale residents in Edgewood and River Oaks watched helplessly as over 26 inches of water flooded their homes, swept through their streets, and swallowed entire blocks. It wasn’t a fluke. It wasn’t unforeseeable. And it wasn’t just the rain.

Now, two class-action lawsuits are shining a light on what many residents already knew: this disaster wasn’t just about weather — it was about failure.

The recently filed lawsuits, accuse contractors hired by the City of Fort Lauderdale of tearing out critical drainage infrastructure as part of a stormwater improvement project — and failing to install any temporary flood mitigation while doing it. The result? A historic flood made exponentially worse by recklessness.

“It was not complete, and we didn’t have anything in the meantime to keep us from flooding,” said River Oaks resident Ted Inserra, who recalled water rising from the creek, over the curb, and straight into his house.

These lawsuits don’t name the City directly — likely due to sovereign immunity protections — but let’s be honest: the blame leads right back to City Hall (if we had one).

A Failure to Plan — Despite Every Warning

Officials tried to write off the 2023 flood as a “1,000-year storm,” but there was nothing unpredictable about what happened. These are low-lying neighborhoods, long known to be vulnerable, with documented modeling identifying their flood risks.

Moreover, nearby airport expansions increased runoff and flood potential — but no additional protections were installed. There were no pumps, no barriers, and no backup plan while the old systems were ripped out. Nothing but empty promises and political sound bites.

A Broader Pattern of Mismanagement

This isn’t an isolated mistake. It’s part of a longer pattern of infrastructure failure, political dysfunction, and possible corruption in Fort Lauderdale.

Remember the 2019–2020 sewage disaster, when over 211 million gallons of raw sewage poured into our neighborhoods and waterways? That wasn’t just bad luck — it was the direct result of the city siphoning funds away from water and sewer infrastructure for nearly a decade to cover operating costs. Even after warnings from the state and residents, the same commission majority voted to continue the practice, until the Florida Department of Environmental Protection issued a consent order mandating repairs.

Or look at the new Fort Lauderdale Police Headquarters, a $100 million project that has ballooned in cost and is now facing serious structural issues. Independent engineering reports found a bending roof slab and cracking foundation, stating the construction did not meet design specifications. Work was abruptly halted, with no clear fix in sight.

Now add this: former City Manager Greg Chavarria, who oversaw much of the HQ project, quietly resigned in April 2024. Shortly afterward, he accepted a position with KEITH, the same engineering firm involved in that project. This move came just as the Broward Office of the Inspector General issued a scathing report accusing Chavarria of violating the city charter.

That’s not just a lapse in ethics — it’s a case study in how deep the rot goes inside Fort Lauderdale.

Enter “The Bloc”

What do these failures have in common? The same leadership team: Mayor Dean Trantalis, Commissioner Steve Glassman, and Commissioner Ben Sorensen — a group often referred to as “the bloc” “the holy trinity” or the “unholy trinity” depending on who you talk to.

Their tenure has been marked by mismanagement, cost overruns, political theater, and special treatment for insiders — all while the public infrastructure crumbles. Whether it’s the flooding in River Oaks, the sewer disaster, the failing police station, a ridiculous tesla tunnel, never ending debate on a bridge or tunnel for commuter rail, or the delayed $200 million parks bond, the outcome is the same: residents pay the price, and their voices are drowned out by donors and developers.

Neighborhoods like River Oaks and Edgewood — working-class areas with deep roots — are ignored while city money and attention are funneled toward vanity projects, high-end development, and their influential special interest allies.

Insider Favoritism

One of the clearest examples of overreach and insider favoritism came in the aftermath of the 2019 sewer main collapse in Rio Vista. An independent audit found that Commissioner Ben Sorensen made 121 unauthorized calls to staff and contractors, directing them to carry out work well beyond the scope of emergency repairs — including raising roads, narrowing streets, and installing park features.

These actions violated the city charter, which explicitly prohibits commissioners from instructing city staff or vendors. Yet despite the audit’s findings, no disciplinary action was ever taken.

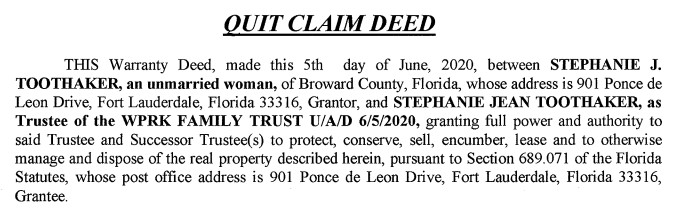

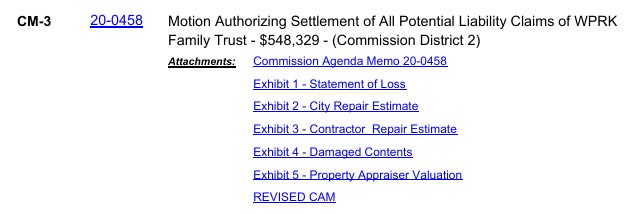

What followed says everything you need to know about how business gets done in Fort Lauderdale. Stephanie Toothaker, a powerful lobbyist and close political ally of The Bloc, owned a home on Ponce de Leon Drive — directly impacted by the sewer break. On June 5, 2020, she quietly transferred ownership of that property to a trust: the WPRK Family Trust. Just one month later, on July 7, 2020, the City Commission approved a motion authorizing settlement of all potential liability claims of the WPRK Family Trust — in the amount of $548,329.

The motion passed without public scrutiny, and because the settlement was issued in the trust’s name, few would have recognized who was actually benefiting. But behind the paper trail, the political connections are hard to miss. The Bloc — Glassman, Sorensen, and Trantalis — approved the payout to a close political ally, without any discussion of the conflict or concern for public optics.

So while insiders like Stephanie Toothaker pocket nearly half a million dollars—thanks to her cozy ties with The Bloc that runs the City—you get nothing. No reimbursement for your destroyed homes. Just a City that hides behind sovereign immunity and Commissioner Sorensen who is too busy rubbing shoulders with wealthy donors in other districts to even show up for his own. That’s what it takes to be heard in Fort Lauderdale these days—because unless you’re in the club, no one’s writing you a check.

The people of Fort Lauderdale are tired of watching their tax dollars disappear into bad projects, broken promises, and backroom deals. From sewage to flooding to failing public buildings, Fort Lauderdale’s infrastructure is a reflection of its leadership. And right now, it’s cracking under the weight. The only question now is—will members of The Bloc, specifically Sorensen and Glassman, who are both anticipated to run for Mayor after Trantalis is term limited, crack as well?

For the life of me, I don’t understand why Sorenson, Glassman are even being voted on sitting on the commission, not to mention Dean

Where is the ethics committee? It is to a point they almost flaunt that they are above the law. If anyone questions as a resident you are treated to a demeaning discourse from the mayor an commission Fort Lauderdale does deserve better an so does the tax paying residents

We need a BIG change in our local leadership. The “Bloc” does not have our best interest in mind.

I hope the residents of River Oaks and Edgewood prevail.

Glassman needs to go.